March 2014

The Epic Survey of Mason and Dixon

Two hundred and fifty years ago, a pair of English surveyors came to the New World to resolve a fierce boundary dispute. The result was an incredible scientific and engineering achievement.

BY DAVID S. THALER, P.E., F.NSPE

More than two centuries ago, two English surveyors arrived in America to help settle a long-raging boundary dispute between the colonial proprietors of Maryland and Pennsylvania. Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon’s epic five-year effort was the first geodetic survey in the New World and would turn out to be the greatest scientific and engineering achievement of the age.

Their story begins with Sir George Calvert, who was the secretary of state to King James I of England. For his loyal service to the crown, he was given the title of Lord Baltimore and granted land in the Americas, which he named Maryland in honor of Queen Henrietta Maria.

The royal charter granted Lord Baltimore all the territory from the Atlantic Ocean “unto the true meridian of the first fountain of the River Potowmack” and from the south bank of the Potomac River to include all land “which lieth under the Fortieth Degree of North Latitude.”

The other players in this drama were members of the Penn family. Sir William Penn had been a distinguished admiral in the Royal Navy who had loaned the profligate King Charles II the then-stupendous sum of 16,000 pounds sterling. In exchange for discharging the debt, his son, also William, was granted the province of Pennsylvania. Penn’s charter granted the land from the 42nd parallel of latitude down to the 40th, excluding a 12-mile circle around the town of New Castle in what is now Delaware.

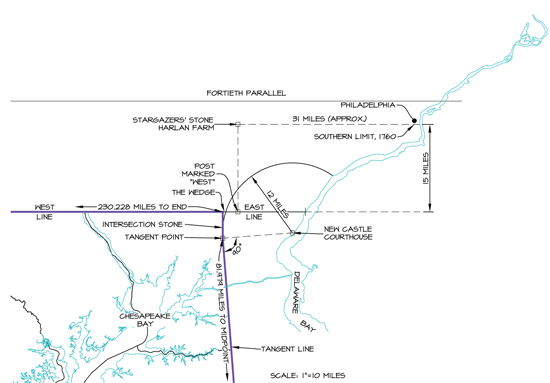

So Calvert, the proprietor of Maryland, was granted from the Potomac up to the 40th parallel and Penn, the proprietor of Pennsylvania, received from the 42nd down to the 40th parallel to where it intersected a circle, 12 miles from New Castle. But the question was, where was the 40th parallel?

Unfortunately for the proprietors, the maps at the time were based on the exploration of the Chesapeake region by Captain John Smith in 1608, and the Smith map showed the 40th parallel too far south. In fact, the 40th parallel of north latitude does not intersect a 12-mile circle around New Castle but lies much farther north. It was this discrepancy that set off the granddaddy of all boundary disputes, which raged for more than 80 years.

The dispute was so bitter because the stakes were high. There were about 4,000 square miles of territory in question, and Philadelphia, which had been settled at the limits of navigability of the Delaware River, lay about five miles south of the actual 40th parallel. Depending on the location of its border, Pennsylvania could have lost both Philadelphia and its critical access to the sea and ability to resupply.

Finally pressed by the king’s council, in 1732 the parties entered into an agreement. They decided that the boundary should run 15 miles south of Philadelphia (the east-west line), west from Cape Henlopen on Fenwick Island to the midpoint of the Delmarva peninsula (the transpeninsular line), and then north to intersect a tangent with the 12-mile arc around New Castle (the tangent line). This was not a good deal for the Calverts, as it placed the boundary about 19 miles south of the true 40th parallel. The controversy raged on.

The parties could not come to a resolution, and finally in 1735 the Penns filed a complaint in the English courts that became known as the Great Chancery suit. The case was litigated over 15 years at enormous expense, until in 1750 a decision was rendered.

The southern boundary of the lower three counties of Pennsylvania (now Delaware) would be at the latitude of Cape Henlopen, and the peninsula would be divided equally. The center of the 12-mile circle would be measured as a radius from the center of New Castle (which was agreed to be the dome of the courthouse), and the east-west line would run at a constant parallel of latitude, 15 miles south of the southernmost point of Philadelphia.

The proprietors engaged local surveyors who started with the transpeninsular line in April 1751. They began on Fenwick Island and ran their line across the peninsula from the “verge” of the Atlantic Ocean to the Chesapeake Bay. Although swamps and dense vegetation made work on the line difficult, the colonial surveyors were able to find and mark the midpoint of the peninsula, which became the southwestern corner of what is now Delaware.

The colonial surveyors next tackled the task of running the tangent line, which ran from the midpoint of the peninsula to the point of tangency with the 12-mile circle around New Castle. This was a lot harder than it looked on paper given that the line was more than 80 miles long, the terrain difficult, and the equipment poor.

The geometry of the corner was also very complex. An 83-mile-long line would have to be run to just graze the 12-mile circle at a perfect 90 degrees. This would then have to be run north to intersect another line exactly 15 miles south of Philadelphia.

The colonial surveyors ran their line from the midpoint of the peninsula due north until it was within the 12-mile radius. Then they measured from the dome of the courthouse, but their first attempt was a half mile too far east.

Two other attempts were too far west. As the task seemed beyond the capability of the local surveyors, the Penns and the Calverts consulted the Astronomer Royal, who recommended Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon. Dixon was an experienced surveyor from County Durham, England, and Mason had been an assistant at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. They had worked together on the Transit of Venus observation of 1761, an international scientific effort to determine the distance from the earth to the sun and the size of the solar system—burning questions of the 18th century.

Mason and Dixon entered into a contract with the proprietors and arrived in Philadelphia on November 15, 1763, to begin work.

They brought with them two state-of-the-art instruments specially commissioned by the Penns for the task. The first was a zenith sector, the most advanced instrument for determining latitude of its day. It had a six-foot telescope mounted over a protractor scale used to determine latitude by measuring the angles of reference stars from the zenith in the sky. They also brought a transit and equal altitude instrument that determined true north by tracking stars where they crossed the meridian.

Mason and Dixon also used other instruments, including a Hadley Quadrant, an octant used in celestial navigation that can measure angles up to 90 degrees, and an astronomical regulator, a pendulum clock in a tall case.

The men began their historic task at the southernmost point of Philadelphia, the north wall of a house on Cedar Street (now under the bed of I-95).

From complex astronomical observations, Mason and Dixon determined their latitude to be 39°56’29.1” N. This became the reference for the east-west line, which would become the Maryland-Pennsylvania border, and was 15 miles due south from their starting point.

Because going the required 15 miles due south to start the east-west line would have taken them across the Delaware River and through the Province of New Jersey, the surveyors decided to proceed west 31 miles, to the farm of John Harland in what is now Embreeville, Pennsylvania, or as they put it, in the “forks of the Brandywine.”

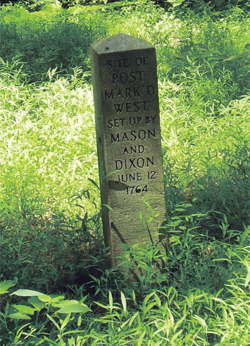

In the spring of 1764, they set off exactly 15 miles due south to a point where they set an oak post, which they called the “Post Mark’d West in Mr. Bryan’s field” near what is now Newark, Delaware. This was to become the starting point of the famous west line and the reference point for the rest of the survey. As it was used as a base for the calculations that followed and is mentioned almost daily in their journal, it is the most significant point in the survey.

After setting the Post Mark’d West, Mason and Dixon then headed south to the middle point of the peninsula that had been previously marked by the colonial surveyors. Following a convenient star, they ran a dead straight line 83 miles from the midpoint, a feat that had never been accomplished before. By measuring their error at the end and proportioning it back along the length of the line, they were able to set the tangent line. They measured the angle at the tangent with their Hadley Quadrant, and the angle measured a perfect 90 degrees. Mason and Dixon had successfully found the solution that had eluded the colonial surveyors.

In March 1765, a year and a half after their arrival, they returned to the Post Mark’d West to begin the monumental task of running the west line. Off they went, hacking their way through the primal forests of western Maryland. They travelled in wagons, the delicate instruments atop a feather mattress. As they went, Mason and Dixon set boundary stones. Mile stones were marked “M” on the Maryland side and “P” on the Pennsylvania side, and they set “crown stones” every five miles with the coat of arms of the Calverts on one side and the seal of the Penns on the other.

After nine months of work on the west line, they had proceeded 117 miles, 12 chains, and 97 links from the Post Mark’d West. (Like other surveyors of their day, Mason and Dixon measured with a chain that had been standardized at 66 feet and was divided into 100 links.) They stored their instruments, returned back east to the Harland Farm where they spent the winter, and then resumed in the spring.

On June 18, 1766, Mason and Dixon reached the Allegheny Mountains, which was the frontier—the western limit of English sovereignty and the beginning of Native American control. Negotiations with the Indians proceeded slowly, but finally, greased by a payment of 500 pounds sterling, a treaty was signed and permission secured to proceed beyond the Alleghenies.

In July 1767, the Indians dispatched three Onondagas, eleven Mohawks, and an interpreter to guide the survey party, which had now grown to 115 men. Early in October, the party crossed Dunkard Creek, where they encountered the Great Warrior Trail. This was one of the most important Indian trails in the country, running from New York to South Carolina. The Indians’ chief informed the surveyors that the trail “was the extent of [his] commission from the Chiefs of the Six Nations and that he would not proceed one step further westward.”

Mason and Dixon continued on and extended their line an additional 250 feet to the top of the next ridge, Brown’s Hill. After the surveyors set up a tall post and a conical mound at 233 miles, 17 chains, and 48 links from the Post Mark’d West, the Mason-Dixon line came to an end.

Having finished their work, Mason and Dixon returned to Philadelphia, where they drew a map of their survey. Two hundred copies were printed.

The magnitude of Mason and Dixon’s accomplishment is almost impossible to imagine. They spent nearly five years in America, living in tents and enduring searing summers and frigid winters. Today, we use GPS to calculate a latitude in minutes. It took Mason and Dixon two weeks of celestial observation and complex hand calculations to accomplish the same task.

Long before chain saws were invented, they used hand axes to clear a vista 16 feet or so wide and more than 330 miles long. Their line has been resurveyed many times, and the accuracy that they achieved, given the technology of their day, continues to astound.

Mason departed for home on September 11, 1768, the work complete. He wrote in his journal “at 11h 30m A.M. went on Board the Halifax Packet Boat for Falmouth. Thus ends my restless progress in America.”

Dixon returned to his family and surveying practice in County Durham, where he died in 1779. Mason returned to America in 1786 with his wife and eight children. He died shortly thereafter and is buried in an unmarked grave in the Christ Church burial ground in Philadelphia.

However, the surveyors’ line lived on.

In 1820, Congress adopted the Missouri Compromise and first used the term “Mason-Dixon line” to describe the Maryland-Pennsylvania border. States north of the Mason-Dixon line were to be free, and those south slave states. And so in addition to being the first geodetic survey in the New World and one of the greatest scientific and engineering achievements of all time, the Mason-Dixon line became an icon—the dividing line between slavery and freedom.

David S. Thaler, P.E., F.NSPE, is president of D. S. Thaler and Associates Inc., a civil and environmental engineering firm in Baltimore. A Fellow of the American Society of Civil Engineers and a licensed surveyor, he is also a guest scholar at the University of Baltimore School of Law, where he lectures on land use.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: THE TRANSIT AND EQUAL ALTITUDE INSTRUMENT USED BY MASON AND DIXON FOR THEIR EPIC SURVEY. TODD BABCOCK

THE TRANSIT AND EQUAL ALTITUDE INSTRUMENT USED BY MASON AND DIXON FOR THEIR EPIC SURVEY. TODD BABCOCK

MONUMENT MARKING THE “POST MARK’D WEST IN MR. BRYAN’S FIELD” NEAR NEWARK, DELAWARE.

MONUMENT MARKING THE “POST MARK’D WEST IN MR. BRYAN’S FIELD” NEAR NEWARK, DELAWARE. THE MAP OF THE SURVEY PREPARED BY MASON AND DIXON AND SIGNED AND SEALED BY THE 12 BOUNDARY COMMISSIONERS, INCLUDING COLONIAL GOVERNOR HORATIO SHARPE FOR MARYLAND AND BENJAMIN CHEW FOR PENNSYLVANIA. Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society

THE MAP OF THE SURVEY PREPARED BY MASON AND DIXON AND SIGNED AND SEALED BY THE 12 BOUNDARY COMMISSIONERS, INCLUDING COLONIAL GOVERNOR HORATIO SHARPE FOR MARYLAND AND BENJAMIN CHEW FOR PENNSYLVANIA. Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society THE AUTHOR WITH MASON AND DIXON’S TRANSIT AND EQUAL ALTITUDE INSTRUMENT.

THE AUTHOR WITH MASON AND DIXON’S TRANSIT AND EQUAL ALTITUDE INSTRUMENT.