December 2013

LEADING INSIGHT

PEs and Professional Duty

It’s time for a renewed emphasis on obligation.

BY GERALD EMISON, PH.D., P.E.

Have you ever gone to work when you really didn’t want to? I suspect we all have; and by doing so we were observing a sense of duty that we have towards our work, our profession, our families, or ourselves.

Have you ever gone to work when you really didn’t want to? I suspect we all have; and by doing so we were observing a sense of duty that we have towards our work, our profession, our families, or ourselves.

I want to suggest that duty plays an important role in dealing with difficult and complex professional challenges. As a result, it deserves more attention in the conduct of professionals.

As an engineering student, I studied amphibious warfare, and I have been haunted since: Why did the marines at Tarawa get out of the boats? I believe that duty played a major role; duty perhaps to the flag, to their buddies, or to themselves. While thankfully most of us are not asked to put our lives on the line, we are asked to persistently do the proper thing in the face of daunting obstacles. I suggest that we often do this, not because of a pay plan or legislative oversight or an overbearing boss but out of a sense of duty, a sense of obligation. Our current efforts to manage professionals neglect this, and our institutions’ performances often reflect this ignorance.

The Western canon speaks to duty. Marcus Aurelius said, “It is thy duty to order thy life in every single act.” Thomas Aquinas observed, “Duty involves obedience to the moral law.” These foundations of Western thought recognize that we instinctively need duty. Professionals can tap this force for good as well as for effectiveness.

I suggest that the future of our society, which relies on our professionalism, depends upon duty becoming an enlivening force in our own lives. As a result, we professionals should place at the heart of our professionalism a dedication to awakening duty in our colleagues, our employees, and ourselves. Yet we overlook duty and rely on individual orientation through pay for performance and accountability rather than appealing to the best in human nature that duty evokes. I believe duty is why professionals often endure difficulties. We would be wise to build on that. Peter Drucker advises us that effective executives build on strength. One strength for professionals is duty, but we often overlook it.

During World War II, U.S. Marines wait aboard a Coast Guard manned combat transport at Tarawa for the invasion barges that will take them ashore. Beyond the rail, Coast Guard coxswains can be seen maneuvering loaded barges.

During World War II, U.S. Marines wait aboard a Coast Guard manned combat transport at Tarawa for the invasion barges that will take them ashore. Beyond the rail, Coast Guard coxswains can be seen maneuvering loaded barges.We currently emphasize pay for performance, but we cannot budget enough to pay for enduring motivation. Oscar Wilde said, “A cynic is someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.” We cannot put a price on the duty of public service, but we most certainly can put a value on it. Similarly, we emphasize accountability, a soft word for finding and punishing mistakes. As a result, our institutions perform below expectations as we call for even more of what did not work before. We are overlooking the enlivening nature of duty and the value of bringing the core of duty into our professional lives.

This core of duty has three aspects: The need for duty, the actions of duty, and the cautions of duty. These three are relevant to professional engineers because we hold the special responsibility to apply complex skills on behalf of others who lack such skills.

The need for duty begins at the need to question the status quo. Our institutions have more exertion and less accomplishment than we wish. The economic collapse of 2008–09 was a failure of duty by Wall Street wizards to care for those beyond themselves. Environmental regulation is a response to the failure of polluters to act on their duty to protect others from their harmful behavior. Congress and its financial gyrations provide an ongoing demonstration of partisan self-interests trumping duty to the common good.

There are institutions we trust and that have performed well. These institutions place duty at the center of their culture. In the past ten years, our military has performed in an exemplary manner. As a Vietnam veteran, I am gratified we today appreciate the value of those who place doing their duty ahead of comfort and safety.

In a completely different setting, the importance of duty was identified by John Brehm and Scott Gates in Working, Shirking, and Sabotage, their 1997 study of effective social service delivery. The major factor in such effectiveness was identified as the culture of an agency in which accomplishing the mission in the face of social and financial obstacles was paramount. The employees did their duty.

The need for duty is spurred also by accelerating change. This change is driven especially by technology and demographics. In technology we see data processing, data analysis methods, and new methods of communicating change daily. Today’s demographics show continued change with generational differences of millennials, Generation Xers, and boomers. Similarly, if we turn our attention to ethnicity we find more diversity, and gender roles rarely are stable.

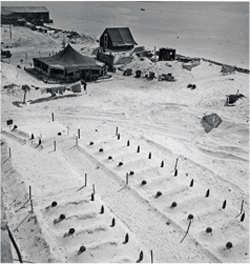

What role did duty play in the invasion of Tarawa? Empty helmets and spent artillery shells mark the graves of marines who fell in March 1944.

What role did duty play in the invasion of Tarawa? Empty helmets and spent artillery shells mark the graves of marines who fell in March 1944.Such evolving conditions suggest that modern professionalism is so complex that we must rely on intrinsic motivation and the sound judgment of workers for success. We have little choice but to rely on values to direct organizations, people, and results. W. Edwards Deming said you cannot inspect in quality, yet we persist in ever more complicated overhead to do so. Deming called on us to build in quality from the outset, and motivating employees through duty enables that.

If there is a need for duty in our profession, there are actions of duty that are simple in concept but difficult in execution. The primary is to build a pervasive sense of duty in everyone with whom we work. As a senior executive in the U.S. government, I sought to move my organizations towards excellence, and these efforts relied upon duty. I had to clarify values, meaning, and purpose of my organizations. It was important to speak clearly, frequently, and openly about values and purpose. While doing so, I had to rely also on the voice of behavior to reinforce my message. This required conveying authenticity that is undeniable: Managers must care and insist that others care.

The importance of these actions of duty was summarized by David McCullough, the prominent historian. When asked what American history teaches about the traits of effective leaders from Washington to Truman, McCullough unhesitatingly named three attributes: Leaders know their stuff, leaders take care of their people, and leaders are honest and responsible. You will undoubtedly note that these attributes are grounded on a common source—duty.

We must be mindful of the cautions of duty. We must avoid becoming static in our practices. The world is changing, and we must constantly adjust and adapt our practices, but not our principles, to current conditions. It is essential to avoid becoming unquestioning or smug: As things change, we must challenge the conventional wisdom because effectiveness under present conditions is what we seek, not comfort with previous practices. We must hold onto what works but experiment to find improvements.

In conclusion, we professionals need a renewed emphasis on duty as a central feature of our conduct. This is because duty is fundamental; it is pragmatic and it is proper.

Duty is fundamental; it taps into a basic human need—the need for meaning in our work. As the future evolves, an emphasis on duty offers our best chance to adapt successfully. Duty is pragmatic; it works. History is replete with difficult tasks achieved through duty. Accomplishing future tasks depends upon exercising duty. Duty is proper; it is moral. It builds on our better nature and affirms people. In a time of mistrust it is authentic duty that enlivens us as humans and connects us to others.

As we practice our profession, I propose that we turn to duty to lead our organizations and direct our own actions. If we do, together we can benefit our children’s future, enrich our own present, and honor the past sacrifices of those such as the marines of Tarawa.

Gerald Emison, Ph.D., P.E., is a professor of political science and public administration and president of the Faculty Senate at Mississippi State University. This article is adapted from Emison’s speech at the NSPE 2013 Leader Conference and Annual Meeting.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: