May/June 2020

Communities: Government

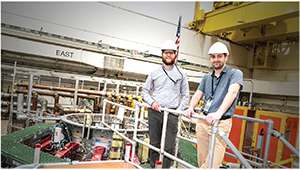

Young Engineers Find Fulfillment at Fusion Lab

ROTATIONAL ENGINEERS BILL HARRIS, E.I.T., (LEFT) AND NICK SANTORO (RIGHT) AT THE TOP LEVEL OF THE NATIONAL SPHERICAL TORUS EXPERIMENT-UPGRADE (NSTX-U) TEST CELL. PHOTO BY ELLE STARKMAN/PPPL OFFICE OF COMMUNICATIONS

ROTATIONAL ENGINEERS BILL HARRIS, E.I.T., (LEFT) AND NICK SANTORO (RIGHT) AT THE TOP LEVEL OF THE NATIONAL SPHERICAL TORUS EXPERIMENT-UPGRADE (NSTX-U) TEST CELL. PHOTO BY ELLE STARKMAN/PPPL OFFICE OF COMMUNICATIONSCommercial fusion energy is not yet a reality. But scientists and engineers have long been working toward the realization of the powerful, carbon-free energy source. At the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, “rotational engineers” can contribute to that goal while gaining broad real-world experience in a variety of different roles. The program also serves as a recruitment tool for the Department of Energy lab devoted to fusion research.

The participants in the program rotate through four six-month positions over two years. Two rotational engineers started last June, and new ones are being added each year. They learn a range of engineering skills and receive mentoring, and they’re encouraged to pursue PE licensure.

According to Principal Engineer Michael Viola, P.E., a 40-year lab veteran and mentor for the program, the relationship is “symbiotic.” Opportunities for the engineers range from basic design and CAD to analysis, fabrication, assembly, and operations. In return, the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory receives the up-to-date knowledge of early-career engineers who will, ideally, want to stay at the end of their rotation. The engineers are full-time, but not permanent, employees.

PPPL engineering department head Valeria Riccardo designed the program based on a similar one in the UK, where she is a chartered engineer. “The idea is that they start with a more rounded view of what working in engineering is,” she says. “Then they choose what they want to do later. It gives them some more maturity and experience than jumping into a job and sticking there.”

In New Jersey, mechanical engineer Nick Santoro was bored in his job at a construction company. He didn’t feel like it related closely enough to the skills he’d spent money to learn in school. He saw a job posting for the rotational engineer program and decided to try it.

Santoro started in a plasma-facing components group, “a little apprehensive” because he didn’t know anything about plasma physics. But after a while he became more comfortable. “Walking down the halls, hearing people actually talk about mechanical drawings and analysis,” he explains, “things I didn’t really hear at the last place I worked, I felt pretty fulfilled right away.” He’s now in diagnostics, helping to ensure sensors are assembled correctly.

One lesson Santoro has learned: Unlike in school, real-life problems don’t always have a concrete solution. But he’s been able to bounce ideas off coworkers who are knowledgeable and have years of experience. “That was exactly the kind of thing I was looking for,” he says. Feeling like his ideas have been respected and he’s been contributing productively, Santoro wants to stay at the lab after his rotations are completed. He also wants to work toward his PE, saying it shows “I’ve proven I’m competent at what I do.”

Bill Harris, E.I.T., finished his master’s degree through a five-year engineering program and was drawn to the PPPL initiative by the opportunity to do hands-on work. So far, he’s worked on designing a fall protection system for technicians with a PPPL team on a diagnostic system for an international fusion project in France called ITER (Latin for “the way”). PPPL is working on behalf of US ITER, which oversees US contributions to the project and is part of a 35-nation coalition.

Harris likes the variety in the days; some include analysis and design, some require hand calculations with his textbook, others are spent in meetings. He praises the institutional knowledge of the engineers who have been at PPPL for decades, like Viola.

After encouragement within the program, Harris passed the FE exam. He was allowed to take time off to study and given resources to do so. “I saw the FE as putting my money where my mouth was,” he says. “To challenge my fundamental knowledge [and] reinforce what I learned.”

Harris hopes that at the end of the program he will have gained well-rounded institutional knowledge from the lab. He already sees that happening—and, after close to a year, is starting to realize his strengths and see how he can help. He also wants to continue at PPPL because the lab’s rotational engineers are given responsibility and treated like full engineers.

Viola praises the “sharp, well-qualified” engineers, who he says came up to speed within a week or two and have already contributed a “tremendous amount” to the lab. “Both are talented individuals and really dove headfirst into the challenges they were given,” he says. “I was concerned they might get a little bored. It’s sometimes hard to keep up with their capability.”

Other organizations could benefit from two-year rotational engineer programs, Viola believes. They lower the pressure, he says, because you’re expecting participants to learn. “They don’t have to fluff their feathers and be the best. With that pressure gone, they flourish.”

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: