May/June 2018

Communities: Government

Lessons Learned from ‘One Water’

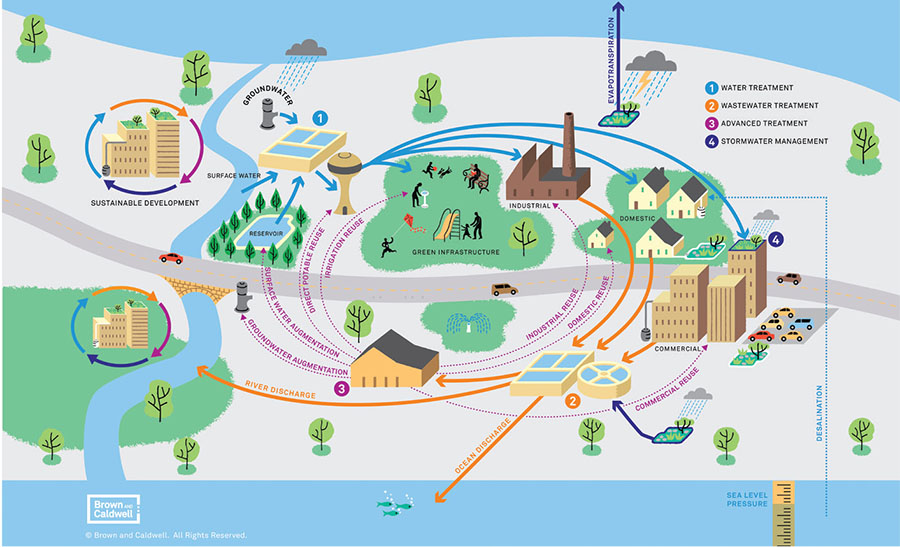

THE ONE WATER CYCLE, AS ENVISIONED BY BROWN AND CALDWELL, WHICH WORKED WITH THE WATER RESEARCH FOUNDATION ON GUIDING DOCUMENT BLUEPRINT FOR ONE WATER. SEE A LARGER VIEW IN PDF

THE ONE WATER CYCLE, AS ENVISIONED BY BROWN AND CALDWELL, WHICH WORKED WITH THE WATER RESEARCH FOUNDATION ON GUIDING DOCUMENT BLUEPRINT FOR ONE WATER. SEE A LARGER VIEW IN PDFBefore the advent of modern drinking water treatment and disinfection in the US, water-borne diseases regularly claimed lives. President Abraham Lincoln lost his 11-year-old son to typhoid believed to have been contracted from contaminated water at the White House. Such history explains the traditional rule of keeping wastewater separate from drinking water and the overall community, Water Research Foundation CEO Rob Renner, P.E., explains.

But that perspective is being revisited with another strategy that looks at and works with all types of water together. The “one water” approach, also known as integrated water management, is not new but has been gaining proponents over the years. Previously siloed components such as wastewater, drinking water, groundwater, surface water, and storm water can all be viewed as a holistic system.

As Michael Mucha, P.E., vice chair of the US Water Alliance’s One Water Council, explains, the perspective emphasizes that “all water has value.” That can result in specific strategies such as recycling wastewater into drinking water, but it more generally means thinking of water as a whole integrated system. Water never goes to an abstract “away.”

One water is earning more attention as challenges such as droughts, flooding, changing climate, aging infrastructure, and water affordability become more prevalent. A one-water strategy can increase efficiencies and reduce costs, as well as improve resiliency and sustainability.

In Los Angeles, Lenise Marrero, P.E., is the project manager for One Water LA, which is defined as a “collaborative approach to manage the city’s watersheds, water resources, and water facilities in an environmentally, economically, and socially beneficial manner.”

She explains that the plan—which includes rain and storm water, groundwater, wastewater, recycled water, and drinking water—is “stakeholder-driven.” From the start, it has incorporated more than 250 stakeholders representing over 150 organizations.

For example, 13 city departments with water-related projects are included in that tally. They have been involved from the beginning to discuss integration opportunities, obstacles, and hurdles. This is a process of culture change, Marrero says: “making sure that everyone has water in the back of their minds when starting to plan a project or program within the city.”

Stakeholders can help ensure that plans consider the triple bottom line—economic, environmental, and social. It’s important to have voices in the room that represent all viewpoints, explains Marrero, the assistant division manager for wastewater engineering services at LA Sanitation. While involving so many people in planning can be challenging, she continues, it can be done. “We don’t necessarily come to consensus in all decisions, but we try to balance all perspectives in all decisions made.”

Mucha, chief engineer and director at the Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District in Wisconsin, emphasizes that an integrated approach places a high priority on building relationships. That may require going a little slower, he says, to focus on shared interests.

He provides this example: Madison gets drinking water from well sources, which results in hard water. Local citizens use water softeners that contain salt; 112 tons a day has to be treated in wastewater. One solution would be to build a bigger treatment plant. But the sewerage district is taking a more collaborative approach, participating on a joint sustainability team with the drinking water utility that is discussing solutions to such issues, including moving to a surface water supply.

Mucha explains that, as a PE, he’s used to relying on technical solutions. But one water emphasizes building smarter over building bigger.

Another lesson learned for both Mucha and Marrero is the need for integrated plans to be adaptive. Mucha suggests experimenting on a small scale while monitoring results. Then apply lessons learned to an improved solution.

Marrero highlights the “trigger-based” approach of One Water LA that ensures flexibility. The plan includes different scenarios; depending on what happens in the future, the city can launch a different suite of projects. For example, what projects can be implemented if regulations for direct potable reuse are adopted? What strategies can increase indirect potable reuse if they’re not?

Mucha’s definition of one water: “Respect every drop.” We can’t create more water, he says, so we need to care for it. “View it holistically, and you become a steward of water as a resource.”

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: