March/April 2019

Communities: Education

Educating 21st-Century Engineers Through Empathy

BY JOACHIM WALTHER, PH.D., NICOLA W. SOCHACKA, PH.D., SHARI E. MILLER, PH.D.

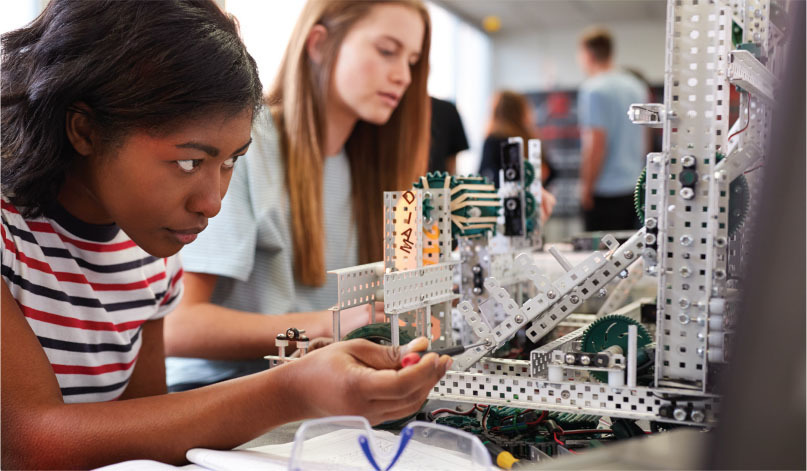

In the 21st century, the grand challenges we are facing as a global society are incredibly complex and deeply enmeshed in social conditions and dynamics. For future engineers, it is thus becoming increasingly crucial to be attuned to the needs and experiences of a diverse range of stakeholders, including those who are directly and indirectly affected by their designs.

A recent study by Google identified qualities crucial to operating in today’s highly collaborative work environment. The best-performing engineering teams were those that had high levels of “social sensitivity”—the ability to pick up on and respond to the feelings and viewpoints of others.

The degree to which engineering programs cultivate these qualities is, however, debatable. In fact, a study conducted by Dr. Erin Cech, a sociologist at Rice University, found that over the course of their studies many engineering students tend to gradually cast aside their concern for the welfare of the public, and for understanding how people use and may be impacted by technology. This trend has been attributed to engineering education’s relentless emphasis on solving technical problems, and the corresponding lack of focus on nontechnical skills, such as ethical reasoning and empathic perspective taking.

Responding to this challenge, our interdisciplinary team of educational researchers from engineering and social work at the University of Georgia developed a new theoretical foundation and pedagogical approaches to foster empathy in engineering. The work combines prior research from social psychology and emerging research in the neurosciences to develop a context-appropriate way of defining and applying empathy to engineering settings, and informing the culture of the profession.

A Model for Empathy in Engineering

The model defines empathy as a skill, an orientation, and a professional way of being.

The skills dimension comprises neurobiologically anchored cognitive functions and thus draws on students’ natural abilities to take others’ perspectives. These skills, or what students can do, can be developed through specific exercises in a classroom setting.

The orientation dimension contextualizes these skills in a set of broader orientations of engineers toward others, and the experiences and different forms of knowledge that they bring to an engineering project. These orientations frame students’ ways of drawing on empathic skills in engineering practice settings—or, in other words, what students will do in a given situation. Situated application exercises can make these dispositions visible in a classroom and open to critical examination by students.

The professional way of being dimension describes a range of broader commitments around the purposes and values that underpin individual students’ trajectories of becoming engineers. These ways of being, or who students are as engineers, provide the foundation for students to effectively embody the orientations and skills dimensions of empathy. Empathy exercises alongside critical reading and role-play activities make these ways of being experientially accessible and offer students opportunities to purposefully reflect on their own professional formation.

Teaching Empathy in a Mechanical Engineering Course

Drawing on this theoretical understanding, we have designed a series of empathy modules that help students develop specific empathic communication skills and explore their application to engineering scenarios. These exercises draw on the pedagogical traditions of social work—a professional discipline that teaches empathy as a core professional tool. One of the modules, for example, guides students to develop critical self-awareness in interacting with others through a series of body language and proximity exercises. Guided role playing in realistic practice scenarios provides students with opportunities to apply the learned skills in an engineering context.

This year, for instance, students engaged in a role play of a stakeholder consultation meeting set in the context of the Flint water crisis. Students who played various stakeholders practiced the skill of perspective taking; students who took on the role of the engineer tried out strategies to purposefully attend to both the emotional and informational content of the conversation, a skill defined as mode switching. Carefully moderated, in-class debriefs were used to immediately make sense of these experiences, then students were invited to further reflect on their learning in individual online journals.

The series of four empathy modules has been integrated into an engineering and society course that is a compulsory part of the design sequence in the University of Georgia’s mechanical engineering program. The course has significantly impacted the learning experience of several generations of students in the largest engineering program at UGA, and has also been the site of an interdisciplinary educational research project funded by the National Science Foundation. The findings from this work continue to inform the development of educational interventions and are being transferred to other settings, such as the integration of empathy training in engineering service learning programs.

Educational Research Findings

The implementation of the empathy modules at UGA provided the context for an educational research study that examined what role empathy plays in the ways students develop as working engineers. Drawing on reflection activities and other course artifacts, the research team collected a comprehensive data set from a total of 110 students. Using qualitative research methods, these data were examined for patterns that can help researchers and educators better understand students’ experiences and how they make sense of them.

Expanding previous thought about empathy development in engineering, the study found that students can be purposefully supported to develop empathic communication skills through carefully designed exercises and thoughtful facilitation.

The data further showed that the development of empathic skills is inextricably linked to, and dependent on, the orientations and values students bring to their interactions with others. In other words, the ways in which they think about their own position, the role of others, and the purpose of the interaction profoundly impacts the ways in which students are able to embody and develop empathic ways of engaging with others.

For educators facilitating this type of professional development, the findings mean that teachers and learners need to attend to these orientations and values and recognize that those discussions often concern elements of emotions and attitudes rather than an intellectual understanding of learning content.

A second main finding highlights the importance of the educational and disciplinary cultures that form the context in which students make sense of their experiences. The data revealed that some of the prevalent understandings of, and messages about, engineering can provide points of tension when students engage with the empathy exercises and associated reflections.

A definitional focus of engineering activity on problem solving, for example, can imply to students that attending to stakeholders with genuineness in the problem definition phase is not part of their role. They are consequently at risk of not embodying or practicing the empathic skills that are the basis for productive and collaborative relationships with stakeholders that 21st-century engineering often requires.

The research also showed that engaging with empathy in the engineering context makes broader aspects of students’ professional formation experientially and pedagogically accessible. In other words, when students practice empathic skills in an engineering class, the personal aspirations, values, and ways of thinking that inform their own trajectory of becoming an engineer are made visible and can be experienced.

This opportunity allows students and teachers to productively engage with the orientations, attitudes, and professional self-perceptions that will determine how students bring both their communication and their technical skills to bear on the grand challenges of their professional futures.

Joachim Walther, Ph.D., is the founding director of the Engineering Education Transformations Institute (http://eeti.uga.edu) at the University of Georgia. He conducts research in engineering education and co-leads an interdisciplinary research group that brings together professors and graduate and undergraduate students from engineering, art, educational psychology, and social work.

Joachim Walther, Ph.D., is the founding director of the Engineering Education Transformations Institute (http://eeti.uga.edu) at the University of Georgia. He conducts research in engineering education and co-leads an interdisciplinary research group that brings together professors and graduate and undergraduate students from engineering, art, educational psychology, and social work.

Nicola Sochacka, Ph.D., is the associate director of EETI and co-leads the Collaborative Lounge for Understanding Society and Technology (CLUSTER), a transdisciplinary research group at the University of Georgia committed to investigating the social and environmental justice dimensions of engineering education and practice.

Nicola Sochacka, Ph.D., is the associate director of EETI and co-leads the Collaborative Lounge for Understanding Society and Technology (CLUSTER), a transdisciplinary research group at the University of Georgia committed to investigating the social and environmental justice dimensions of engineering education and practice.

Shari Miller, Ph.D., is the associate dean in the School of Social Work at the University of Georgia. She conducts research related to professional education for reflective and effective practice in a sustainable local and global society.

Shari Miller, Ph.D., is the associate dean in the School of Social Work at the University of Georgia. She conducts research related to professional education for reflective and effective practice in a sustainable local and global society.

Empathy Model

A model of empathy in engineering includes three interconnected dimensions of skills, orientations, and professional ways of being.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: