January/February 2014

COMMUNITIES: EDUCATION

Does Engineering School Lower Student Concern for Public Welfare?

Colleges and universities, despite their efforts to graduate engineers with not only technical skills but also a broader concern for serving the public, may inadvertently be creating a “culture of disengagement” about public welfare, according to a new study.

Colleges and universities, despite their efforts to graduate engineers with not only technical skills but also a broader concern for serving the public, may inadvertently be creating a “culture of disengagement” about public welfare, according to a new study.

Erin Cech, an assistant professor of sociology at Rice University, surveyed more than 300 engineering students at four institutions (which are unnamed for confidentiality purposes): a large state school, an elite tech school, a private liberal arts college, and an engineering-only college. Across the board, the results held—and they have attracted attention.

Cech discussed her work with PE.

PE: Can you provide some background on why you wanted to do this study?

As a double major in electrical engineering and sociology, I was always interested in the interplay between the engineering profession and the larger social world. As I moved into research and as a sociologist, I noticed a lot of talk within the engineering education community and those who study [it] about the need to develop more well-rounded, socially conscious engineers. There have even been changes to engineering accreditation toward this end. There is an increasing agreement among engineering educators and the engineering community at large that engineers need to have a broader knowledge base than just math and science skills.

In light of this, the research question I asked was, do engineering students actually graduate more concerned with public welfare issues than when they entered [school]?

PE: Can you elaborate on what you found?

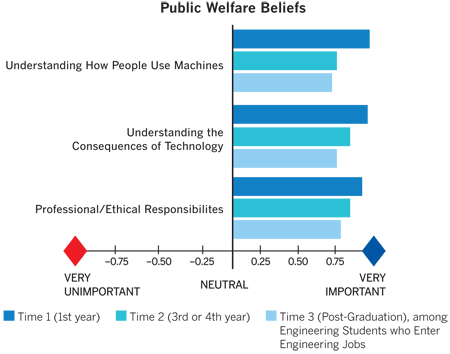

I looked at four different indicators of public welfare concerns: the importance to them of their professional and ethical responsibilities, of understanding the consequences of technology, of understanding how people use machines—and their broad social consciousness. I asked the set of questions when they came in as freshmen and then later on in their engineering education—their third or fourth year—and then a third time, for those that went into engineering jobs, 18 months after graduation.

What I found, on all of these measures, is that their public welfare concerns declined significantly from the time they entered as freshman to the later time points.

PE: Were you surprised by the results?

PE: Were you surprised by the results?

I was surprised by the extent of the decline and the across the board nature of the decline. Based on literature and some prior research, it didn’t seem outside the realm of possibility. I expected the beliefs might remain stagnant, but the decline was kind of disconcerting.

PE: Can you elaborate on possible causes?

This is not a case of cold-hearted people within the engineering profession. What I think is going on is a broader issue of what is valued within the culture of engineering broadly and in engineering education in particular. There are three ideological pillars that help uphold this culture of disengagement.

The first I call depoliticization, or the belief that issues of culture and politics not only can be separated from more technical work but should be. Depoliticization tends to bracket discussions of public welfare and social issues from engineering classrooms. [Students are] assigned problems to solve with little or no engagement with broader contextual concerns. These issues are often [pushed] into engineering ethics classes that might meet once a week for a semester.

The second pillar is the technical-social dualism, the idea that technical skills and social skills are separate and mutually exclusive. The technical skills are far more valued than social skills like communication and writing, but both are, of course, vital for success as an engineer.

The third pillar is the meritocratic ideology, a popular belief in engineering, and in society more broadly, that advancement systems are fair and just—the people who have the most talent and drive succeed and those that don’t have such drive and talent don’t. People who hold the meritocratic ideology blame individuals for their own social disadvantages rather than the broader system. Such a belief makes conversations about public welfare seem illegitimate, especially within engineering contexts. If poverty is the fault of the poor, then should engineers be involved in doing anything about it?

These three ideologies are beliefs that are salient in engineering more broadly and permeate engineering education as well. Students learn these ideologies and learn to identify with them through the process of becoming engineers.

PE: What’s the solution?

Because this is not an issue of a few bad engineering education programs but a broader cultural issue, it becomes difficult to have a silver-bullet solution.

There needs to be more integration of public welfare concerns into traditional engineering content. [One possibility is to] add questions related to public welfare into homework assignments and tests. Students’ demonstration of [reflection] and knowledge on these issues becomes part of what’s graded. This would help to make these issues legitimate topics within engineering education and give students practice at developing skills to think critically about them.

When I was an engineering student, I would sometimes use things I was learning about in my sociology classes, such as issues of access and equality, to ask questions in my engineering classes. Such questions were seen by my professor and classmates as really odd.

But those are the kinds of concerns that engineers actually have to deal with when they go into the workforce. Being an engineer in the real world doesn’t involve the kind of sanitized questions that students get in homework assignments and exams. They have to face the complexities of the real world when they graduate.

I’m not arguing for a weaker engineering or something less pure, but training engineering students to be better prepared to go into the workforce where they have to deal with public welfare complexities all the time.

PE: Are there next steps with this research?

An important next step is to not only see if these processes are in play in a wider sample of engineering programs but also what might be effective in trying to undermine these patterns, and to look at the pedagogical implications of increased engagement. I’d also be interested in the extent to which public welfare [outlooks] change the longer people are in the workforce.

This is the first study of its kind. It’s meant to be a starting point for further research. Because of the sample size, it can’t be the final word, but it is a way to start the conversation.

I would reiterate, I’m not looking to deconstruct engineering or engineering education. I don’t have a personal vendetta. I’m interested in producing better engineers, engineers that are equipped to go out into the world and have the intellectual tools necessary to do the work they are faced with.

PE: What are the implications if this isn’t addressed?

To give you an example, I was having a conversation with a computer scientist, a graduate student at a different university. He and his colleagues in the lab were designing facial recognition software that could be used by autistic children to learn what emotions were expressed through facial movements.

He was telling me that a group of high school students from a lower-income school were touring the lab. Several couldn’t get the tool to work. One said, “It doesn’t work on black people.” He was right. All the people in the lab were white. No one had thought to try it on someone whose skin pigmentation wasn’t like theirs.

That kind of thinking not only potentially produces technology that can exclude whole parts of the population, but it’s also bad engineering. It doesn’t do what it’s supposed to do. By bringing in thoughts about public welfare concerns and the effects of technologies on people, it opens up a whole other set of considerations that can make technologies better.

Cech’s paper “Culture of Disengagement in Engineering Education?” appeared in the January 2014 issue of the journal Science, Technology, and Human Values.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: