January/February 2014

COMMUNITIES: GOVERNMENT

Dam Failures Created California’s ‘Gold Standard’ Safety Program

State’s program offers model as the number of high hazard dams increases nationwide.

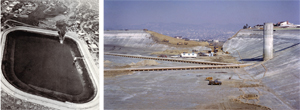

A little over 50 years ago, knocks sounded on the doors of Baldwin Hills, California, residents. The local dam was leaking—they had to evacuate immediately. Four hours after the earthen dam first showed signs of failure, it split. Two hundred fifty million gallons of drinking water poured out of the reservoir. Five people lost their lives; others were dramatically rescued via helicopter. The water, which left a square mile of mud and debris behind, destroyed or damaged at least 250 homes.

While the disaster was not the first high-profile dam failure in California history (the St. Francis dam failure in 1928 killed an estimated 400–600 people), it was the first time that such an event was broadcast live on television. Together, those failures, as well as the near failure of the Lower San Fernando Dam during an earthquake in 1971, shaped the development of California’s dam safety program. It now serves as the model for other states and is deemed the “gold standard” by the Association of State Dam Safety Officials’ executive director, Lori Spragens.

In Baldwin Hills, settling of the area along the weak zone of an inactive earthquake fault line caused the failure. David Gutierrez, P.E., chief of the California Division of Safety of Dams, explains that nearby oil operations could have been the underlying reason for the land subsidence but the official investigation did not firmly reach that conclusion.

But the disaster also brought attention to the need for offstream reservoirs to be brought under the division’s jurisdiction, and legislation after the failure did just that. Gutierrez explains that Baldwin Hills demonstrated that failure of water storage facilities located within cities can be just as catastrophic as failure of those located at water sources.

California’s dam safety program, launched in 1928, is one of the oldest in the country. It is also the largest in the country in terms of budget and employees, with 49 civil engineers in the division plus geologists and administrative staff.

California has emphasized dam safety for several reasons, says Gutierrez. One is that the state is the most populous in the nation; hundreds of thousands of people may live downstream of a dam. In addition, California stores water for summer irrigation, creating the need for huge dams. And the state’s high potential for earthquakes adds safety complexities.

Despite these factors, the dam safety chief says his division has to continually remind the legislature and the public of the importance of dam safety, especially as the office works to make failures just a memory. As of 2003, the state’s general fund no longer helps finance the program—it is now fully funded through annual and construction fees paid by dam owners.

The California division, which contributed to a model dam safety program developed by the Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) and sponsored by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), tries to inspect every dam every year. Gutierrez realizes that not every state has the resources to do that, but he says waiting longer increases the cost of repairs.

The PE says that nationally, dam safety has come a long way in the last decade or two, but “we can’t lose focus.” In 2013, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave dams in the country a grade of D, a rating that ASDSO participated in. Spragens notes that a lot of state dam safety programs are under-resourced.

In addition to expressing concerns about deficient dams, the organization is paying attention to the number of high hazard dams (those with potential for fatality if a dam fails), which is growing as people move into downstream areas.

ASDSO is pushing for the reauthorization of the National Dam Safety Program. FEMA operates this national coordination program, which also provides grants to states. “We are really encouraging—more than encouraging—all of Congress to get [the Water Resources and Reform Development Act] passed so the safety program can be put back in place,” says Spragens.

“We have a vision that all dams will be safe in the US,” she says.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: The failure of the Baldwin Hills dam in 1963 was one of the key events that helped shape California’s dam safety program.

The failure of the Baldwin Hills dam in 1963 was one of the key events that helped shape California’s dam safety program.