January/February 2015

Losing Our Memories

The engineering collection at the National Museum of American History is stagnating. Without intervention, important connections to the past may be lost forever.

BY EVA KAPLAN-LEISERSON

At the National Museum of American History, you can view the flag that inspired the national anthem and Dorothy’s ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz. But there you can also examine a Thomas Edison lightbulb, a Nikola Tesla motor, and one of the country’s earliest steam locomotives on a section of the first iron railroad bridge.

Part of Washington, DC’s Smithsonian Institution, the museum holds more than three million objects, documents, and photographs in trust for the American people—including a well-developed collection of engineering- and technology-related items. That is, dating to about mid-twentieth century. The recent past is another story.

Despite the country’s current STEM focus, the museum’s civil and mechanical engineering collections have not had a designated curator in more than a decade. That means key modern developments aren’t being collected or displayed. Soon it may be too late.

Government Cutbacks

The Smithsonian Institution is the world’s largest museum and research complex, comprising 19 museums and galleries, nine research facilities, and the National Zoo. It was created by Congress in 1846 after a sizeable bequest. Currently, the institution is about 60% federally funded, with the remainder made up of revenues from commercial enterprises and private contributions.

American History Museum staff know they have a problem, and they want to fix it. The issue comes down to money. As the government has tightened its belt over the decades and especially in recent years, the museum has had to follow suit, letting attrition thin its workforce.

Between 1992 and 2014, the number of curators, collections specialists, and archivists there dropped by almost half, to 58 from 113.

The Division of Work and Industry, where most of the engineering artifacts are housed, includes curators who concentrate on electric power and lighting and railroad transportation. However, the last staffer focused on the civil and mechanical engineering collections retired in 2003.

The collections are not in any imminent danger—existing items are well taken care of. But no one is focused on adding, documenting, or promoting items.

History’s History

Robert Vogel, civil and mechanical engineering curator for 31 years, developed much of the collections. He joined the museum in 1957 and left as the last person with a full-fledged curator title.

Vogel had graduated from architectural school but never practiced. After serving in an Army Corps of Engineers construction battalion, he became interested in the history of engineering and technology.

Vogel’s early years were the “golden age” of the museum, he says. Congress had received appropriation in the mid-1950s for both the new building on Constitution Avenue and staff.

The building opened in 1964 as the Museum of History and Technology. As curator, Vogel had several key responsibilities: designing galleries, collecting objects, researching and writing about the artifacts, and answering public inquiries. He was largely left alone to make decisions.

In considering how to cover civil engineering in a small (now defunct) gallery, Vogel decided to emphasize bridges and tunnels and display them through models. For instance, he commissioned a model of the Permanent Bridge of Philadelphia and one showing portions of the Brooklyn Bridge.

The civil engineering gallery was removed about 15 years ago to make space for the America on the Move transportation exhibition. But the other area that Vogel was responsible for developing, the Hall of Power Machinery, remains. It is the oldest existing exhibition in the museum, greatly unchanged since the building opened.

Vogel worked hard to fill this hall as well. It includes items large and small, ranging from the 1926 Skinner Universal Unaflow Engine that runs almost the length of one room to batteries dating from 1805.

When asked what he is most proud of from his three decades at the museum, the longtime curator responds, “That’s like answering who’s your favorite child.”

Generally speaking, he continues, his biggest achievement was adding to the previously existing collections: not only models but also documentation such as drawings, specifications, and records.

A Static Present

Vogel keeps an eye on the museum—his wife still works there. He describes the engineering collection as “not growing, not diminishing…in stasis.”

Peter Liebhold is the chair of the Division of Work and Industry and the closest thing the civil and mechanical engineering collections currently have to a curator. Growing up, he planned to become an engineer, but then became the “classic engineering school dropout.”

“I loved the discipline, but I didn’t fit in,” he says. Instead, he decided to focus on history, and his enthusiasm is palpable as he shows off a sampling of items in a back room.

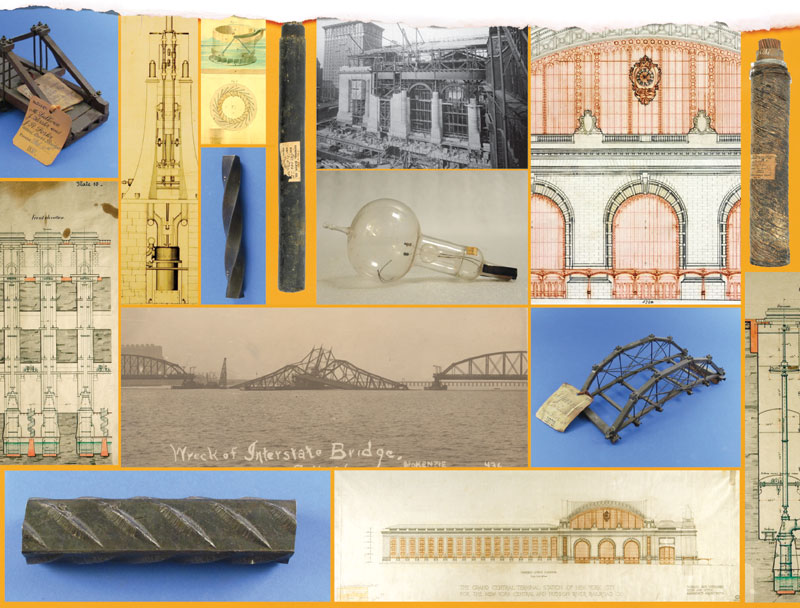

Mid-1800s drawings from a Baldwin locomotive demonstrate the shift to specifying design and interchangeability of parts, he explains. “It’s unlikely that you would ever find something earlier and more significant than these,” gushes Liebhold. “If you like drawings, this is totally cool.”

Early pieces of rebar he calls “pretty.” Holding one attempted design, he says, “You could turn it into jewelry or something.”

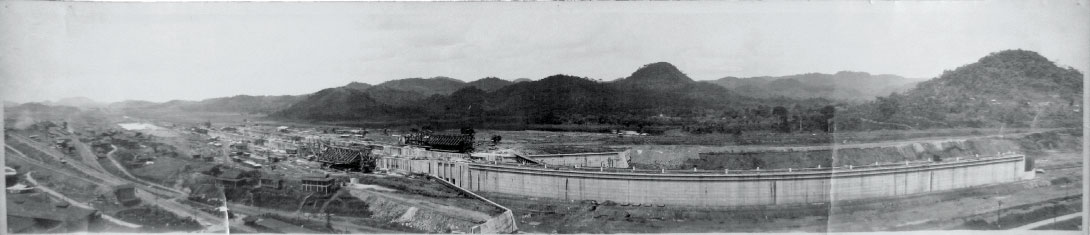

Liebhold shows a panoramic photo of the Panama Canal. Elsewhere is kept a hinge ball for one of the gates. He illustrates a photo of one of the engineers who worked on the canal with a story about him. “These should not be faceless people,” he says. “It’s really interesting to know who they are, what they do.”

He points to elevation drawings for New York’s Grand Central Terminal and Washington, DC’s Union Station. A lot can be learned from these, Liebhold notes. “It’s not just a question of, can you reproduce it, but it shows how things are organized, what the specifications [and materials] were like.”

One of the last items Liebhold highlights is a book, Scene by the Engineer: Remarkable Prints from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, published in 2005. “But if you flip through this, you see it’s strong in the 19th century, early 1900s, and then the book ends…[in] 1941,” Liebhold says. “That kind of represents our collection.”

Exceptions exist, such as the concrete pieces of the New Orleans levee wall that failed during Hurricane Katrina and flooded the Ninth Ward. (The museum aims to portray failures as well as successes.) But on the whole, the newer items in civil and mechanical engineering are few and far between.

It’s not like engineering development stopped in the 1950s, says Liebhold. There are “incredible things that are going on. But we’ve not done nearly as much because we didn’t have the staff to do it.”

A Space to Fill

Only a tiny percentage of the engineering artifacts can be displayed at any given time. There is a great deal that the public cannot access. A dedicated curator, Liebhold explains, could create focused exhibitions as well as gather input on what should be collected.

In the first half of 2013, Allison Marsh, a professor in the University of South Carolina’s department of history, temporarily joined the museum staff through a fellowship funded by Goldman Sachs. Marsh’s father is a PE and she holds an undergraduate engineering degree from Swarthmore College. She had worked for several years as an engineer before pursuing a PhD in the history of technology.

Marsh’s role was to assess the engineering collections and help plan for the future. She reiterates the lack of modern additions. “The last couple of decades may have had a few advances,” she says facetiously. “Just a few.”

For instance, both she and Liebhold stress the need to collect items related to the changing energy picture, such as artifacts illustrating fracking. Despite its controversy, the technology advance is important and should be represented, Marsh says.

She highlights two broad, and contrasting, themes that she believes a curator should be concentrating on: 1) globalization—multinational companies working on really big projects, and 2) very local stories—how engineering affects every single person. “That’s one of the challenges of the museum,” she says. “To make that knowledge visible.”

For instance, late 1800s drawings from the first US water purification plant, in Milwaukee, are some of her favorite items. “We take clean water for granted,” she says.

She also spotlights the engineering notebooks and business receipts for the building of Grand Central station. Contractors writing “We need to order more concrete” or “We are over budget” help put the drawings in context, she says.

A curator’s challenge, she explains, is to collect in the present those artifacts that will be important in 50 years. For instance, if failed technology isn’t collected now, it will be lost. Specialized knowledge can also die out.

It’s key, she says, to think about what was a game changer versus just a minor improvement. Sometimes it’s obvious, she continues, but other times more unpredictable. That’s why a professional curator who understands both how things work and the larger technological context is critical.

The Larger Picture

Both Liebhold and Marsh discuss the need to make more visible the role of engineers and engineering. The museum wants to do that, but the strategy has changed. Instead of focusing specifically on how things work, Liebhold explains that he aims to answer, “Why does this matter?” That puts engineering into a bigger framework as an important part of society, he says.

So instead of having a “Hall of Engineering,” which he believes would appeal to engineers but few others, he wants to integrate the profession into the bigger context of American history. “If you say that engineering is key to your existence, that you would not be what you are today if you didn’t have engineers, then you get everybody,” he says. “You suddenly realize that engineers are really what drive everything.”

That’s the way to get “your aunt from Syracuse” to care, he adds, and also to help create a more informed citizenry that better understands the past and the way it contributes to the future.

Liebhold is working on putting together a new 8,000-square-foot exhibition that will incorporate engineering into the larger story. American Enterprise, scheduled to open in July, will focus on four major themes: opportunity, innovation, competition, and the common good.

For instance, the Generating Change section, spotlighting the electrical side of the Industrial Revolution, will contain Edison lightbulbs, electric cable samples, and metering and generation systems.

A Green Business section will include a case study on the modern-day efforts of SC Johnson—known for brands like Pledge, Windex, and Ziploc—to avoid coal-fired power plants and choose sustainable energy sources such as wind power. Liebhold himself collected a scale model of one of the turbines.

Future Planning

The museum has repeatedly requested an engineering curator and includes the position as a key need in its five-year curatorial plan. Leaders hope to regrow the workforce through a combination of federal support from the Smithsonian’s annual budget and private-sector fundraising. The museum is running a capital campaign through 2017: an endowed curator position would cost about $5 million.

Liebhold feels optimistic. “Hopefully we’ve hit bottom and are moving back up,” he says.

As Marsh wrote in a June 2014 Issues in Science and Technology article, “Collective Forgetting,” about the needs of the engineering collection, “[The Smithsonian’s] curators help us access and interpret our country’s collective memory.”

And she believes engineering is a critical area to celebrate. “[Engineers’] work is what matters,” she says.

Liebhold notes that it’s easy for the public to not appreciate what engineers do. If the roads and bridges are working fine, engineering isn’t given a second thought, he says. “Success often does not breed great respect.”

The National Museum of American History wants to change that—but it needs help to do so.

How to Help

While the museum can always use monetary support, Liebhold also emphasizes the need for engineers to become collaborators and contribute their expertise. He’d love to hear suggestions of engineering developments and the “rock star” engineers of today who are critical to include.

NSPE members could also help by offering public programs, such as lectures or demonstrations, at the museum.

There’s an additional opportunity to contribute items. “What we want people to do is to give us the ruby red slippers of engineering,” Liebhold says. Marsh adds that a good artifact provides a compelling personal side to a larger American story.

E-mail [email protected] with your ideas. We will pass them along to the National Museum of American History and publish a sampling in an upcoming issue.

Learning From History

The National Museum of American History strives to demonstrate the relevance of the past to the present and future. The museum’s department of education and outreach is working with collaborators to do just that in a new project aimed at middle school students.

Using 3D models of early inventions and roadmaps to reconstruct them, students will learn groundbreaking engineering in an accessible way, says education specialist Matthew Hoffman.

His department is teaming up with the Smithsonian’s 3D digitization group as well as the University of Virginia’s Lab School for Advanced Manufacturing Technologies, which partners with local public schools, and Princeton University.

Modern technology has a “black box” problem, says Hoffman. It’s both physically encased and generally challenging for even professionals to understand. But early inventions are simpler and more transparent, easier to take apart and reverse engineer.

3D models of early inventions, such as the Morse-Vail Telegraph Key, will be supplemented with primary sources, such as journals from Alfred Vail. Kits will enable various levels of re-creation depending on tool availability, from simple items, such as card stock and Popsicle sticks, up to 3D printers.

The project has received some grant funding and is pursuing additional grants. The initial 3D models and invention kits should be posted online at the end of 2015.

Explains Hoffman, the goal is not that students should be able to reconstruct an exact replica of the innovations but understand the science and engineering behind them. They can then apply those concepts to create their own inventions, he continues, and develop “the skills needed to solve the problems of the future.”

Additional Resources

> Information on collections and access to online artifacts: http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/subjects

> Doodles, Drafts, and Designs: Industrial Drawings from the Smithsonian: www.sil.si.edu/exhibitions/doodles

> The Smithsonian X 3D viewer: http://3d.si.edu

> The National Museum of American History’s national campaign: http://smithsoniancampaign.org/unit/national-museum-american-history

FIRST ROW FROM LEFT: WOODEN TRUSS BRIDGE PATENT MODEL, 1880; RAIL MILL ENGINE FOR BETHLEHEM IRON COMPANY, ABOUT 1873; WATERWHEEL PATENT DRAWING, 1838; GENERAL ELECTRIC RUBBER-COVERED POWER TRANSMISSION CABLE, 1897; GRAND CENTRAL TERMINAL UNDER CONSTRUCTION, 1912; PROPOSED ELEVATION FOR GRAND CENTRAL TERMINAL STATION, 1905; GENERAL ELECTRIC THREE-WIRE POWER TRANSMISSION CABLE, 1897. SECOND ROW FROM LEFT: FRONT ELEVATION, PROPOSED HYDRAULIC SCHEME FOR NIAGARA FALLS, 1890; CONCRETE REINFORCING BAR SAMPLE; THOMAS EDISON DEMONSTRATION LAMP, 1879. THIRD ROW FROM CENTER: WRECK OF THE INTERSTATE BRIDGE IN DULUTH, MINNESOTA, 1906; TRUSS BRIDGE PATENT MODEL, 1879; CROSS ELEVATION, PROPOSED HYDRAULIC SCHEME FOR NIAGARA FALLS, 1890; BOTTOM ROW FROM LEFT: “KNOXVILLE BAR” REBAR DESIGN; PROPOSED ELEVATION FOR GRAND CENTRAL TERMINAL STATION, 1905.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE PANAMA CANAL

ALL IMAGES COURTESY OF THE SMITHSONIAN’S NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: THOMAS EDISON LIGHTBULB, 1879

THOMAS EDISON LIGHTBULB, 1879 ENGINEER FRANK P. SHELDON NOTEBOOK, PROBABLY 1870S

ENGINEER FRANK P. SHELDON NOTEBOOK, PROBABLY 1870S MORSE-VAIL TELEGRAPH KEY, 1844

MORSE-VAIL TELEGRAPH KEY, 1844 PIECES OF NEW ORLEANS LEVEE WALL, BROKEN DURING HURRICANE KATRINA, AUGUST 2005

PIECES OF NEW ORLEANS LEVEE WALL, BROKEN DURING HURRICANE KATRINA, AUGUST 2005 MODEL OF SC JOHNSON WIND TURBINE, DEDICATED 2012

MODEL OF SC JOHNSON WIND TURBINE, DEDICATED 2012