Spring 2024

Engineering Ethics—How to Hold Your Leader Accountable

BY KYLE PAYNE, PH.D.

When learning about leadership, we get to know leaders of every style imaginable – ethical leaders, servant leaders, transformational leaders, and the list goes on. With so much talk about leaders, it’s easy to forget the important role that followers play, particularly when they’re asked to do something unethical. How do they influence their leader or their peers to do the right thing? A recent study of the engineering profession identified 13 behaviors that followers can use to promote engineering ethics.

In the Spring 2023 issue of PE magazine, I shared the results of a study involving 300 professional engineers in the On Ethics section article, "How to Avoid Doing Bad Things for Good Reasons: Lessons from a Study of Professional Engineers." I explained that, like everyone else, professional engineers "morally disengage" and make excuses for unethical behavior at work and that these excuses predict unethical behavior. Alongside efforts to reduce moral disengagement through training and coaching, I suggested that engineering firms should highlight the stories of ethical followers, or professional engineers who do the right thing despite facing pressure to do otherwise (including pressure from their leaders). In this article, I will summarize a follow-up study of professional engineers and identify 13 ethical follower behaviors that, if modeled and reinforced, can help engineering firms reduce unethical behavior.

I interviewed 25 professional engineers about their experiences navigating ethical dilemmas at work and trying to influence their leader or their peers. The study participants described pressure to provide services that were outside their area of competence. They described pressure to "take shortcuts" or "cut corners," such as substituting materials that are cheaper or can be more readily procured, or skipping important installation or testing steps. They described pressure to mislead clients, whether by making false representations or omitting important information. They also described pressure to approve or sign and seal engineering work without having had the proper control or oversight to do so.

Results of the Study

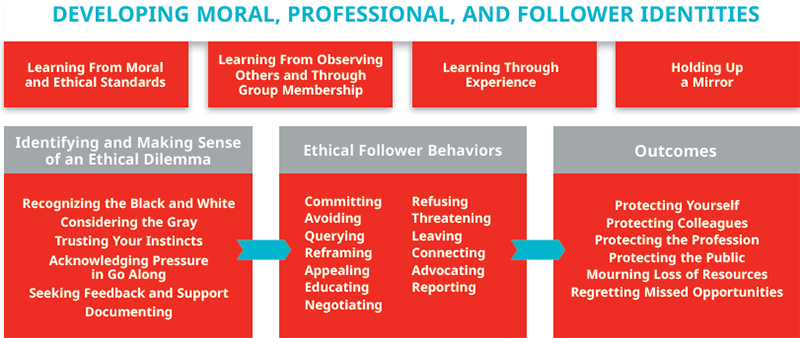

Four categories emerged in the data and are represented in a new theoretical framework for ethical followership. First, Developing Moral, Professional, and Follower Identities explains how professional engineers develop identities related to being a "good person" and a "good engineer," as well as how they develop a sense of their role as a follower, whether in relation to a particular leader or a common purpose. It draws on what professional engineers learn from moral and ethical standards, from observing others and through group membership, and from experience. It also speaks to how they evaluate the extent to which they are living in accordance with their personal moral standards or the ethical standards of their profession.

The second category, Identifying and Making Sense of an Ethical Dilemma, speaks to how professional engineers recognize "black-and-white" ethical dilemmas, which is when the options available and their ethical implications are clear and it’s relatively easy to determine the right thing to do. It also addresses how professional engineers navigate the "gray" ethical dilemmas that are more nuanced and in which the appropriate response is less clear. This category also addresses experiences of trusting one’s instincts, acknowledging pressure to go along with an unethical directive or request, seeking feedback and support from others, and documenting observations and reactions.

The third and fourth categories represent Ethical Follower Behaviors and Outcomes. Ethical follower behaviors refer to actions taken by professional engineers to do the right thing when facing pressure to do otherwise, which I’ll describe in the next section. Outcomes of ethical follower behaviors include protection of the ethical follower, their colleagues, the profession, and the public. These outcomes also include mourning the loss of material or symbolic resources associated with a job, such as a steady income and professional relationships, as well as reflecting on missed opportunities to do the right thing (or to act sooner).

Fostering Ethical Follower Behaviors

Participants described one or more ethical follower behaviors when asked about their responses to unethical directives, unethical requests, or other situations at work where they felt pressured to do something unethical. They also described a behavior of "committing" when they identified someone or something they were highly motivated to follow. Each ethical follower behavior is defined below and explained via examples reported by participants. Each participant is identified by a pseudonym.

Committing refers to the ethical follower embracing a leader’s directive, or request, or influence in a manner that is informed and often enthusiastic. Participants described past and current follower roles in which they were attracted to leaders or teams that demonstrated honesty, trust, and a willingness to consider different perspectives. Nelson referred to his experiences committing to a leader who encouraged followers to disagree and critique his ideas, stating, "He made sure that people were questioning him and holding him accountable as a leader."

Avoiding refers to the ethical follower withholding action on an ethical dilemma while forming their intentions to resist an unethical directive or request in some fashion. Participants described avoiding interactions with a leader and trying to evade further pressure to comply with an unethical directive or request. This behavior involves some degree of what participants described as passively "going along" or "looking the other way" and ignoring unethical behavior within their team. When explaining the rationale for their decision to avoid, participants explained that they were evaluating the best course of action while there was not yet an immediate risk to the safety, health, or welfare of the public. Toby expressed confidence that avoiding would pay off, stating, "I knew that I would find the right time to act and actually be able to make a difference."

Querying refers to the ethical follower asking the leader questions on what they are directing or requesting, or their rationale for doing so. While sometimes used genuinely to gain clarification, this behavior was often described by participants as an attempt to expose and document the leader’s unethicality. As Barnaby suggested, "These guys are specialists in deniability. I wanted him to take responsibility for what he was asking me to do. I wanted to make him say it." Dominic expressed feelings of satisfaction and joy, stating, "It can be entertaining to watch a leader squirm."

Reframing refers to the ethical follower proposing a way of looking at the ethical dilemma from another perspective so as to reveal ethical implications or other options. This behavior was common when a follower could provide a unique perspective on the basis of their knowledge or experience, particularly when the leader was a nonengineer. Zac stated the premise to reframing, noting, "I didn’t expect him to understand the issue inside and out, but I did expect him to listen and consider other perspectives."

Appealing refers to the ethical follower asking the leader to withdraw the directive or request. Typically this approach entailed highlighting the ethical implications of complying with the directive or request. Faced with signing off on a new product that was not ready for market, Penelope described appealing to her manager to reconsider, stating, "I had to get pretty honest and explain that we will jeopardize business for everyone involved and that we can’t afford that risk."

When appealing to a leader, direct and assertive communication is important. As Dino articulated, "It’s a three-step process. You describe what they said, how it made you feel, and what they can do to correct that." This behavior gives an opportunity to the leader to consider the ethical follower’s perspective and determine whether to reinforce the directive or request or to withdraw it.

Educating refers to the ethical follower helping the leader gain knowledge or skills that are critical to making or executing an ethical decision. Given that many participants identified the leader they were trying to influence as a nonengineer or as an engineer from another discipline, much of this education revolves around technical knowledge and putting complex subject matter in lay terms. For example, trying to educate a nonengineer city councilmember, Tom related a roadway construction technique to how the leader might treat a potted plant. Participants also described helping a leader develop soft skills, such as communicating about a sensitive issue or resolving a conflict. Penelope emphasized that approaching a leader to educate them rather than to negotiate or refuse can help "defuse" the situation and "leave people in an honorable way."

Negotiating refers to the ethical follower working with the leader to find a suitable compromise that serves the leader’s interests and the ethical follower’s interests. In Tom’s case, he was asked to sign and seal a design for a 225-ft water tower that originally provided an elevator for technicians to use, but that would now exclude that option to reduce costs. Citing the concern for a technician’s safety and well-being, Tom negotiated changes that would provide some relief for the technician.

Refusing refers to the ethical follower asserting to the leader that they will not execute their directive or request, usually with an explanation of the rationale. In cases where it was required that a professional engineer sign and seal, participants described leveraging the power of the PE license. In an effort to ensure that a report disclosed potential blasting costs for foundation work, Barnaby noted that his license served as "a pretty powerful club" and enabled him to uphold personal moral standards for honesty and integrity. Refusing comes with considerable risk; it resulted in involuntary termination for a few participants who attempted it.

Threatening refers to the ethical follower stating intention to take adverse action, such as Leaving or Reporting, if the leader pursues what they perceive to be an unethical course of action. Whether explicitly stated or implied, this behavior puts the leader "on notice" of potential consequences of their actions. For example, when noticing early signs of sexual harassment of a colleague, Buck advised his leader that he would report the harassing behavior if it continued, indicating, "I’m not going to keep quiet if this continues."

Leaving refers to the ethical follower leaving a business relationship, an organization, or the engineering profession voluntarily in response to an unethical directive or request. For participants who took this approach, the idea of leaving came easily but decisions regarding when and how to leave responsibly, as well as what to do next, were difficult and typically involved detailed contingency planning. Leaving can cause a significant loss of material or symbolic resources associated with a job, such as a steady income and professional relationships.

Recognizing the disconnect he felt with his firm’s culture, Josh explained his rationale for leaving: "You’re going to have to decide. If you can’t change it, then you’re going to have to leave. You’re going to suffer otherwise." When determining whether and how to terminate a relationship with a client due to ethics concerns, Ollie took inspiration from a professional engineer who modeled leaving in a manner that resonated with him. According to Ollie, having observed unethical behavior that was excused by the state licensing board, the professional engineer sent his license to the state with the message, "If this is the way you’re going to let other people work, then this license is not worth the paper that it’s printed on."

Connecting refers to the ethical follower bringing together perspectives from multiple sources that may otherwise be siloed or disconnected from one another. In some cases this technique is used to educate, appeal to, or negotiate with a leader. For example, Justine described being the single client-facing member of her team and encouraging the client to raise concerns in meetings. As she put it, "If the message comes from the client, it has more weight." Connecting may also be used to rally support to collectively respond to an ethical lapse. As Bert described when reflecting on leading a dialogue with his peers, "It’s about strength in numbers. It’s hard when you’re the only person dealing with it."

Advocating refers to the ethical follower contributing to policy or education in one’s organization or profession to elevate the work. These behaviors may focus on general efforts to promote ethical behavior, such as organizing workshops or knowledge-sharing events. They may also be geared specifically to an issue that the ethical follower is concerned about. For example, Josh described a successful effort with other professional engineers to propose and pass state legislation to improve life cycle assessments on infrastructure projects.

Reporting refers to the ethical follower pointing out unethical behavior, or a leader’s unethical directive or request, to an individual or group, or to the public directly as a remedy. There are several ways to report an ethical lapse, but participants generally described a progression. For example, an ethical follower may escalate their concern to a leader’s leader or their human resources department. If necessary, they may further escalate the concern to an outside party like a client, or the media, or a state licensing authority. Participants described seeking feedback and support when determining whether to report and navigating fears of retaliation, and they pointed to the NSPE ethics hotline as a valuable resource.

Conclusion

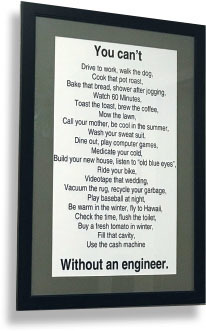

When it comes to reducing unethical behavior among professional engineers, the concept of ethical leadership is deeply embedded in our efforts. That is, to maintain high ethical standards within our firm, we expect leaders to be moral people and moral managers, and we expect them to model for their followers how to conduct themselves. This approach is fine if we can count on every leader being ethical and if we consider leadership as something a leader does and not as something cocreated by leader and follower working together. To enhance our leader-centric efforts, we ought to determine what behaviors we expect of ethical followers and to set them up for success with training, coaching, and support.

, PH.D., IS A LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANT AND PROFESSIONAL COACH IN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, WHO FREQUENTLY WORKS WITH PROFESSIONAL ENGINEERS AND ENGINEERING FIRMS. HE CAN BE REACHED VIA HIS WEBSITE AT WWW.KYLEPAYNEPHD.COM.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: