August/September 2014

IN FOCUS: BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT

Everyone’s Business

Skills such as the ability to bring in work and understand the financials are important for engineers at all levels, not just for company principals.

BY EVA KAPLAN-LEISERSON

PE

recently asked a handful of experts, including both consultants and company leaders, to rate engineers’ overall business skills. The average answer: C.

recently asked a handful of experts, including both consultants and company leaders, to rate engineers’ overall business skills. The average answer: C.

As AEC management consultant John Doehring explains, professionals in general—whether doctors or engineers—are most passionate about practicing their craft. Running the business is often seen as a “necessary evil.” But these skills are important both for companies and individuals’ careers, experts say, and benefit more than just firm heads.

Employees with business skills can help organizations survive and thrive. In return, these skills help make workers more marketable and can expand their employment opportunities.

Trial by Fire

Despite their broad applicability, business skills are not a usual part of an engineering curriculum. NSPE member Eric West, P.E., is a principal for design firm Parkhill, Smith & Cooper and the Society’s 2010 Young Engineer of the Year. West says that he had to learn early in his career that not only would he need to apply the technical skills school taught to solve client problems, but he would also have to help a company make money to keep it going.

West calls learning the business and financial aspects “eye opening” and the learning curve “steep.”

Scott Kupper, P.E., president of Kupper Engineering and an NSPE member, uses the same word to describe his learning curve. When he launched his company in 2004, he and his partners had to learn business skills through trial by fire. “The things I wasn’t taught, I’m learning the hard way,” he says.

Kupper earned an electrical engineering master’s degree, but wishes he’d gotten an MBA instead.

Engineering career coach Anthony Fasano, P.E., didn’t learn business skills in school either. But the Engineer Your Own Success author worked to develop them after realizing their importance to a well-rounded resume.

Fasano became an engineering firm partner at age 27. Now, at 35, he is CEO of his own company—Powerful Purpose Associates—as well as executive director of the New York State Society of Professional Engineers. The PE credits the skills he learned early in his career with his rapid advancement.

Fasano rates the importance of business skills for engineers as very high, nine on a 10-point scale, and says that of the 15,000 or so visitors to his career coaching website each month, more than half are looking for advice on topics such as networking and business development.

Key Skills

According to West, engineers with adequate technical skills but very good business skills have as good or better chances to advance than those with very specialized technical skills. Organizations highly value business skills, he continues.

Want to improve your business skills? Here are some areas to focus on:

Winning work. In many companies, getting to partner means bringing in business, says Fasano. “If you can’t do that, you can’t advance.”

Doehring believes so strongly in the importance of this skill that he rates it even more highly than the ability to execute projects. Admitting that his view is sometimes seen as heretical, he says that he doesn’t want to downplay the importance of technical skills, but instead emphasize that they are just a piece of the overall pie. “Nothing is more important than figuring out what’s necessary to build relationships, win work,” he says.

Kupper believes the best way to do this is through quality results. “The best business development you can have is what you’re doing on a project now,” he stresses. His company hasn’t done much marketing over the years. Instead, the 35-employee electrical engineering firm has grown through reputation and referrals.

Understanding the financials. This includes topics such as profit and loss and reasons why a project or company is succeeding or failing, West explains. For example, understanding how time and expenses on a job affect whether it makes money.

Kupper also points to the importance of understanding the time-money relationship. His company works on many energy projects in which a client is borrowing money from a larger entity, and time is of the essence. “If you don’t meet the financing criteria, [a project] doesn’t work,” he says. “Engineers need to understand that.”

Speaking and writing. Although engineers may struggle with speaking in public, Fasano says, the ability to do so—whether in front of two prospective clients or a hundred people at a presentation—is an important business skill.

Doehring describes both speaking and writing as key ways professionals can market themselves to bring in new business. “Go first, add value, expect nothing,” he says. For instance, write a blog post or give a presentation about a trend in your business. Publish in trade journals.

The consultant warns that some of these methods take time and don’t result in immediate payoffs. “People aren’t necessarily going to call you up and ask where to send money,” says Doehring. But over time, he adds, those steps can be extremely effective ways to position yourself as an expert.

Networking. Good networking requires developing real relationships—not just swapping info at conferences, says Fasano. “You can’t just go to an event and come back with five business cards and think [that effort] will change everything.” Get to know people on a more personal level, he says. Although you might not want to take time away from the office, doing so is necessary to build strong relationships.

In addition, online networking tools such as LinkedIn can help extend your reach, the career coach says. But he emphasizes that using the platform well means active participation, for instance in groups and discussions.

Every Engineer

According to these experts, business skills can no longer be just the purview of top leaders.

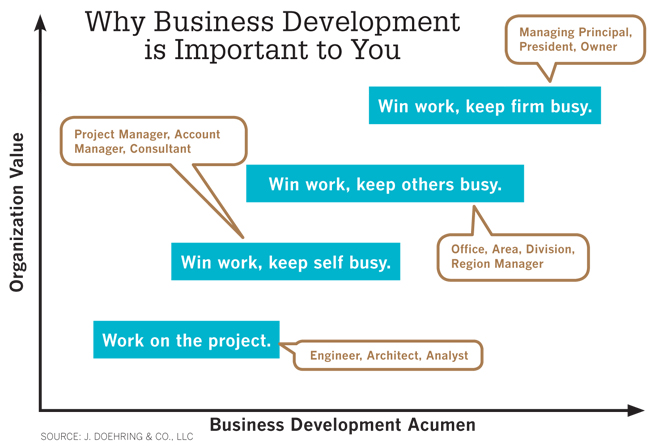

As Doehring puts it, although many engineering companies have traditionally left most business development to company principals, that won’t work in a time when workplace change is accelerating due to factors such as technology and globalization.

If a company is full of technical talent but its employees don’t know how to win work, it could become a commodity, Doehring says. In addition, limiting business skills to the top principals is not a sustainable model, he believes, because it means companies can’t grow much further beyond the capacity of that 5%–10% of staff. And leadership transitions and company sales will be more difficult if only a few people have the knowledge.

According to Kupper, even project engineers need to make sure they’re being responsive to clients and understanding their larger commitments such as schedules. And West says all employees, even if they’ll never be owners, should have a sense of how what they do affects the overall business.

Companies that are transparent about their financial standing enable employees to help, West explains. For instance, engineers can spend more time on billable activities and less on overhead. “A one-hour change per week across a large company can make a huge difference in the overall bottom line,” he notes.

Fasano points to the benefits of business skills for individual engineers, saying that those who can offer them are in the minority. Thus, workers who can provide such value will both better retain current jobs and improve career opportunities overall.

With the economy so up and down, companies could let employees go at any time, he says. Engineers have to ask themselves, “If I don’t have a job in two weeks, do I have the business development skills that I need, am I using LinkedIn properly, have I built up contacts?”

A lot of engineers get comfortable in their companies and think they don’t need these skills, he explains. But then he gets a call from one who’s been laid off, and it’s almost too late to help.

“For all intents and purposes, in today’s world you’re pretty much running your own business,” Fasano says.

Gaining Skills

Although he rates most engineers’ business skills at that C level, Fasano doesn’t blame individuals. “It’s not engineers’ fault,” he says. “We didn’t learn this stuff. How can you be expected to know?”

However, he doesn’t have an easy answer about how people can catch up. “Learning takes time,” he says. Training courses and books can help, but he believes the key is consistency. Watching one video about public speaking won’t be enough.

West says some people at his company have gotten MBA degrees or taken college-level courses. But the method that’s worked for him and others is simply mentoring. He “sat at the feet” of a colleague who had been involved with the business side for decades and gained insight by asking questions, he says.

Doehring believes that students should hear about the importance of business skills much earlier in their careers—even as early as middle school. Engineers don’t progress up the career ladder because they become more proficient technically, he says. Very few firms are owned and run by a chief technical officer.

Schools should tell students, “If you want to be CEO, it’s much more about winning work and running the business than thermo-dynamics and heat transfer,” he says.

For those already in the workplace, Doehring believes trial and error can also play an important role. “The trick is to stop worrying about perfection and pick a few [actions] and start doing them,” he says.

Caveats and Challenges

A common view in engineering is that there is a right way and a wrong way to do things, explains Doehring. “It’s an extraordinarily unuseful paradigm” for business, he continues, emphasizing that engineers should just go out and try building their skills in areas like writing, speaking, and networking.

But companies need to be open to such methods, the consultant stresses. If an organization measures only billable hours, it can’t incentivize people to invest time. “It takes a commitment to the long-term and courage to buck this engineering notion that we can measure each and every day whether or not we were productive,” says Doehring.

In addition, senior management can be reluctant to let junior employees experiment, he says. “There is some pushback.” The management consultant says he continues to evangelize for this, but often a company leader eventually sees that it’s in his or her own interest to allow the experimentation. Changes coming to the industry will make things more difficult, notes Doehring. “If something is hard, you need more people involved, not fewer.”

Going Beyond

Not developing business skills can leave engineers behind, says Fasano, as someone else moves forward.

“I think the successful engineer of the 21st century is someone a lot more well-rounded,” says Doehring. Although he or she will still have technical competency, other contributions such as marketing, business development, and people skills will also be important parts of the mix, he believes.

But, he continues, that’s not much different than today. The very successful engineers at the top of firms are already the ones with these skills.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: