October 2014

Letters

Funding Our Highways

Ohio’s engineers, having just experienced one of the worst winters and wettest spring on record, now have an even bigger storm to deal with. I urge you to stay informed about what’s going on in Washington, DC, the nation’s capital. From all that I have been hearing and reading in national publications, as well as in local hometown newspapers, a highway crisis is looming. As reported, gridlock in Washington will lead to gridlock across the country if lawmakers can’t quickly agree on how to pay for highway and transit programs. This will have a major impact on professional engineers throughout the United States.

In Ohio, legislators have been dealing with the same issue of funding the state’s highway program, as funding generated by the antiquated gas tax formulas continues to dry-up. Numerous reasons for the shortfall of dollars have been identified, yet no one has been able to come up with a plan or solution to make up the dollars lost. Is that the case or is it just too unfavorable to introduce legislation imposing a higher gas tax? You decide. Whatever the reasons, the end result will be continued poor highway infrastructure ratings, bridge postings or, worse yet, closures—all of which will ultimately lead to a loss of professional engineering jobs not only in Ohio but throughout the US.

Pick up a phone or a pen and contact your local legislators. Advocating to your legislators is one of the most important things you can do to protect the engineering profession. Let your legislators know that doing nothing about the impending infrastructure crisis is not an option! A vital part of the Engineers’ Creed references one of the duties of the professional engineer: to protect the public and look out for the health and safety of all.

Joseph V. Warino P.E., P.S., F.NSPE

Vice President of Legislation and Government Affairs

Ohio Society of Professional Engineers

The July 2014 issue contains an article explaining that the Highway Trust Fund is running out of money because Congress has not adjusted the motor fuel tax rates to reflect a) diminished purchasing power and b) more efficient vehicles. The same issue includes an article describing how one state, Oregon, is investigating “pay-per-mile” funding as a substitute for motor fuel taxation (“Oregon First to Launch Pay-Per-Mile Funding Plan,” p. 16).

The July 2014 issue contains an article explaining that the Highway Trust Fund is running out of money because Congress has not adjusted the motor fuel tax rates to reflect a) diminished purchasing power and b) more efficient vehicles. The same issue includes an article describing how one state, Oregon, is investigating “pay-per-mile” funding as a substitute for motor fuel taxation (“Oregon First to Launch Pay-Per-Mile Funding Plan,” p. 16).

While I understand the frustration generated by our government’s seeming inability to adjust the fuel tax rates when needed, I cannot see the logic of substituting a costly, complex, and very invasive (in a personal sense) method of taxation for one that is simple, low-cost, and noninvasive. The fuel tax has the added benefit of rewarding those drivers who use more efficient engines.

To me, the solution should be to enact legislation that will have built-in mechanisms to adjust the tax rates automatically every few years, without the need for congressional action each time.

Joseph Horowitz, P.E.

Flushing, NY

Construction Productivity

I must respectfully disagree (again) with Paul Teicholz and Matt Stevens as to their assertion that construction industry productivity is in decline (“Construction Productivity in Decline,” June, p. 13). On the contrary, my research has consistently found that construction productivity has improved at a rate of approximately 0.8% per year.

Why the difference? It is because Teicholz and Stevens use an invalid measure of output. Constant contract dollars do not accurately measure output of the construction industry for two reasons:

- Tangible output, measured against constant dollars spent, has increased. My research, and that of others, demonstrate that real unit costs (dollars per square foot of building area) have decreased over time.

- Constant dollar measurement of output does not take into account the enhancements in quality and performance of buildings over recent decades. Among these qualitative enhancements are improved safety, sustainability, energy efficiency, accessibility, and others.

If the output measure of mere constant dollars is adjusted for these factors, a very significant increase in productivity results. Further, this is consistent with readily observable increases in productivity made possible by mechanization of earthmoving, concrete placement, and materials handling; labor savings from easier-to-use materials, such as PVC pipe and single-ply roof membranes; computerization of lines and grades, logistics, and jobsite communication; and prefabrication and modularization of building components. All of these—and many more—have driven unit costs down while also producing qualitative improvements in the finished product.

As Teicholz and Stevens point out, there is much more that can be done to continue productivity improvement. But we should not be misled into thinking that positive measures introduced and implemented during the past half-century or so have failed to increase productivity.

Preston H. Haskell, P.E.

Chairman, The Haskell Co.

Jacksonville, FL

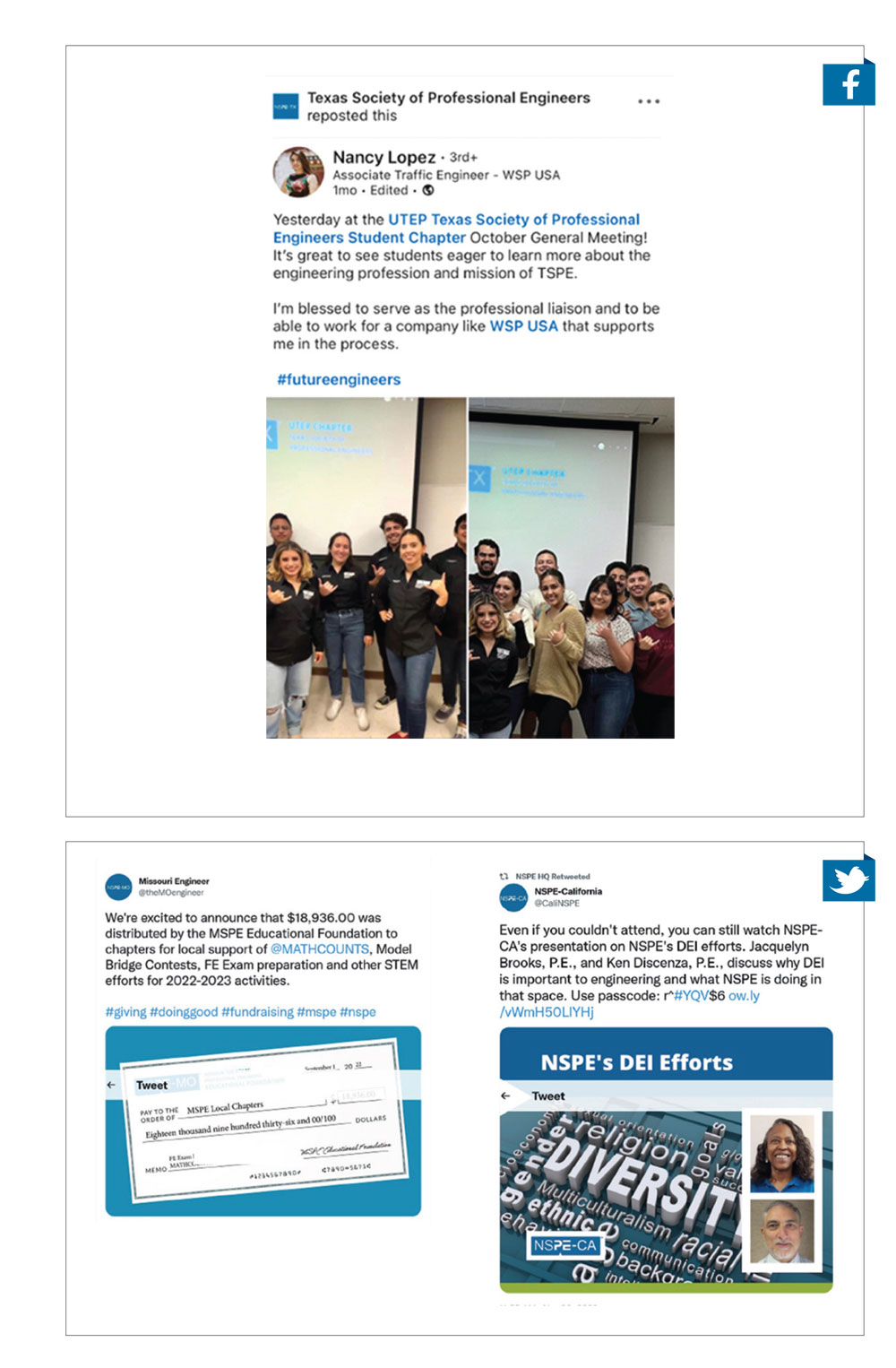

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: