November/December 2018

Variables

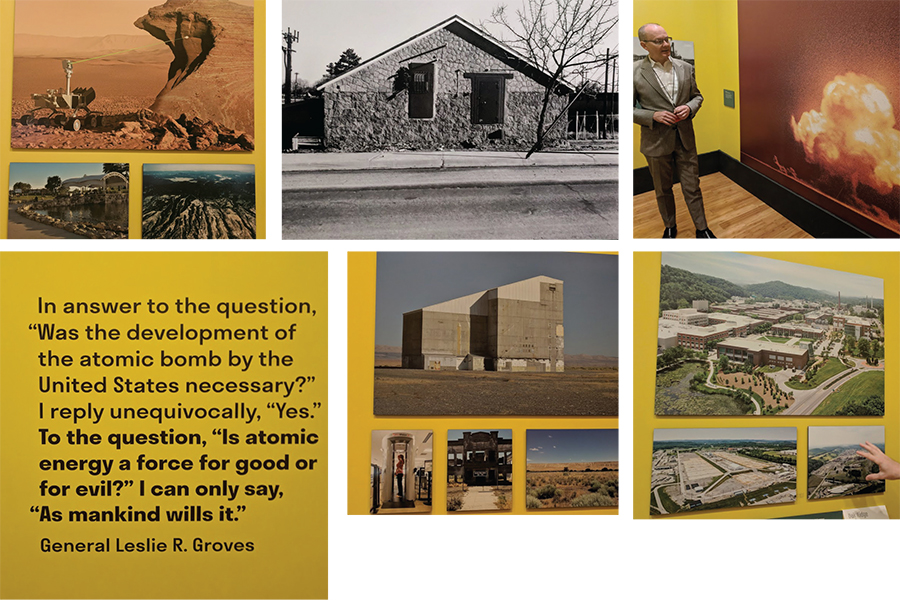

A Look Inside the Manhattan Project’s Secret Cities

The Manhattan Project was one of the most crucial events in world history. The project saw collaboration involving science, government, military, industry, and so much more coming together to move forward with the polarizing plan to construct the first atom bomb and set up the events that ended World War II. But engineers, too, were integral toward the project being a success.

Currently on display at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., the exhibition “Secret Cities” tells the history of the design, construction, and daily life within the cities that were selected as the locations of the Manhattan Project’s main activities. Those include uranium enrichment in Oak Ridge, Tennessee; plutonium production in Hanford, Washington; and finally, the design and construction of the world’s first atomic weapons in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

The three cities were chosen because of their somewhat secluded and remote locations, often surrounded by valleys and canyons, and they were kept top secret from the public.

While the scientific community, under the lead of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, is deservingly credited with their contributions to the project, the National Building Museum also makes it clear in the exhibit that engineers played a critical role in developing the atom bombs.

For starters, Lt. General Leslie Groves, the Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw and directed the project, appointed Oppenheimer and hand selected the sites for research and production. Additionally, A/E firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill was tasked with building many of the makeshift community structures and houses for engineers, scientists, researchers, and their families who lived in the secret cities—some of which still stand today.

“These were not just typical communities that grew up in a haphazard fashion, there was a hand of design there even at the beginning of their existence,” says the museum’s senior curator Martin Moeller.

Additionally, Moeller explains that without the help of qualified engineers, the scientists might not have been able to create the first plutonium production reactor or make the proper vessels (which ended up being the “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” bombs) to hold and store the radioactive fuel inside.

The exhibit also examines the aftermath of the war and its effects on the secret cities, as well as the cultural and scientific effects of the project in the United States and across the globe.

The exhibit, like many of the museum’s offerings, shows an appreciation for the engineering efforts that went into the project as well as offering professional insight that you won’t find at another museum.

The Secret Cities exhibit will be on display until March 2019. Learn more at www.nbm.org.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: