November/December 2018

Communities: Education

Educating the Whole Engineer

By Steven Collins, Ph.D., P.E.

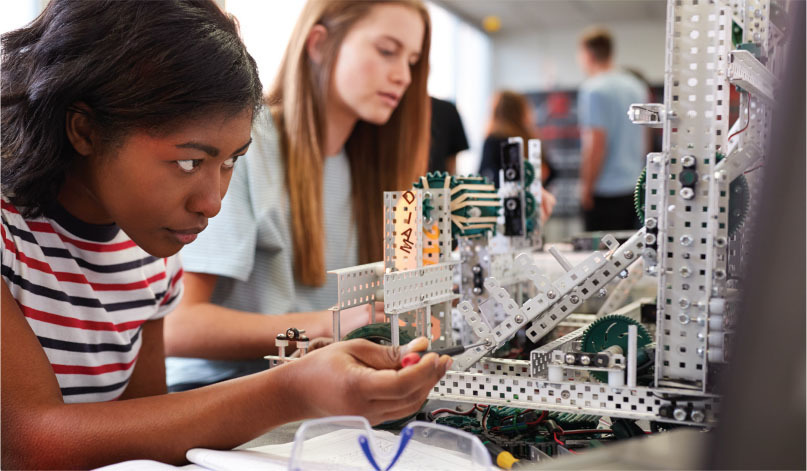

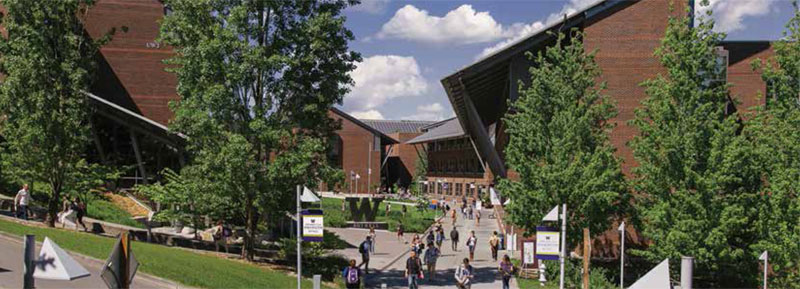

Five years ago, I received the opportunity of a lifetime: design a mechanical engineering major from scratch, for the University of Washington Bothell. The new curriculum was to be grounded in engineering best practices, geared to preparing well-rounded graduates who understand and embrace their ethical and societal responsibilities, and of course aligned with ABET criteria.

Five years ago, I received the opportunity of a lifetime: design a mechanical engineering major from scratch, for the University of Washington Bothell. The new curriculum was to be grounded in engineering best practices, geared to preparing well-rounded graduates who understand and embrace their ethical and societal responsibilities, and of course aligned with ABET criteria.

From the start, ethics and professional practice have been at the center of the mechanical engineering curriculum. Students take not one but two classes in the senior year that focus on the soft skills we believe most distinguish successful engineers. On one level, we sought to infuse the program with the values of the campus, which encourage active, critical engagement with social and political issues. On a second level, we wanted to give our students the best possible preparation to become professional engineers. While we do not require that students take the Fundamentals of Engineering Exam, we strongly encourage it, and we help them prepare.

Professional Engineer is the penultimate course in the senior curriculum, covering professional ethics, communications, engineering economics, and licensure. Guest speakers from the local community describe what PEs do and explain why licensure is necessary. Leadership also receives serious attention. We don’t boil it down to a recipe. Rather we draw from biographies of engineers, past and present, who model leadership excellence. Also covered is professional ethics, including the NSPE Code of Ethics and its application.

Professional ethics resides in a broader context of identities, relationships, and obligations that bind people into communities and connect them with their environments. Citizen Engineer, which precedes Professional Engineer in the curriculum, deals with the nonprofessional obligations engineers have as members of multiple, overlapping communities. Students learn how to apply ethical reasoning to work through ethical dilemmas for which appeal to a code of ethics alone may not be enough.

The thinking that underpins our method runs like this: Before I can be a good engineer, I need to know what it means to be a good person. And to be a good person, I need to understand the different approaches to defining good. Finally, I need to have a conception of the good society before I can use engineering skills to help create it. Professional Engineer thus works hand-in-glove with Citizen Engineer to give students a framework for ethical decision making, of which engineering ethics is but one part.

Our outcomes strongly suggest that the program is succeeding. ABET approved the program as soon as it became eligible for review. To be sure, not all students enjoy the heavy amount of writing and reading, though I’ve been surprised at how many do. For some, being taught societal and ethical implications by an engineer who is also a social scientist motivates them to pay attention, and it differentiates our approach. Although we haven’t tracked numbers for the FE exam, we estimate that roughly one in five or six students are taking it, and the proportion is increasing. I’ve not heard of a student who has failed it.

This past spring, we offered the Order of the Engineer ceremony at our campus for the first time, and more than half of the mechanical engineering graduating class was inducted. I couldn’t have been prouder as I recited the Order’s creed along with them.

Steven Collins, Ph.D., P.E., has taught at University of Washington Bothell since 1993. He holds a B.S. with distinction in chemical engineering and a PhD in foreign affairs, both from the University of Virginia. He is the 2018–19 president of the Washington Society of Professional Engineers.

COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON BOTHELL

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: