June 2014

IN FOCUS: PROFESSIONAL LIABILITY AND RISK MANAGEMENT

The Changing Risks of Going Green

In recent years, green and sustainable building has evolved from trend to standard practice. Some project risks have changed as well.

BY MATTHEW McLAUGHLIN

Six years ago, PE magazine noted that green or sustainable building was “in” for 2008 but warned that design professionals who ignored normal risk management procedures amid the hype at the time could experience increased liability risks. Since that article was published, however, green building has greatly changed, and the liability concerns of 2008 are not all concerns of today.

Six years ago, PE magazine noted that green or sustainable building was “in” for 2008 but warned that design professionals who ignored normal risk management procedures amid the hype at the time could experience increased liability risks. Since that article was published, however, green building has greatly changed, and the liability concerns of 2008 are not all concerns of today.

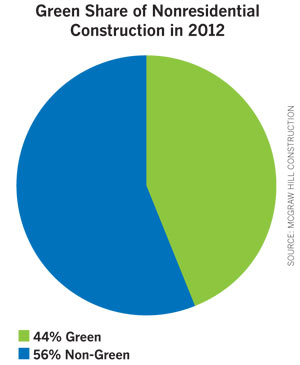

One constant appears to be green building itself. The frenzied interest of 2008 may be gone, but in its place is a genuine interest that is likely to stay. “Green building is becoming standard practice in the United States,” a 2013 McGraw Hill Construction report claims. “Since McGraw Hill Construction started analyzing…data for the green share of nonresidential construction, it has seen the US green building market grow from 2% in 2005 to 44% in 2012.”

The 2008 PE article “Dangers of the Green Rush” cited an American Institute for Architects survey of 661 cities that found the number of those cities with green building programs rose from 22 in 2003 to 92 in 2007. Another survey of those cities just two years later in 2009 found that number had increased by a further 50% to 138. That follow-up survey found 24 of the 25 most populated metropolitan regions in the US were built around cities with a green building policy by 2009.

Green building and sustainability in general had already garnered support from a number professional societies like AIA by 2008, and that support continues. As noted in “Dangers of the Green Rush,” NSPE’s own code of ethics was updated in 2007 in support of sustainable development, which it defines as “the challenge of meeting human needs for natural resources, industrial products, energy, food, transportation, shelter, and effective waste management while conserving and protecting environmental quality and the natural resource base essential for future development.”

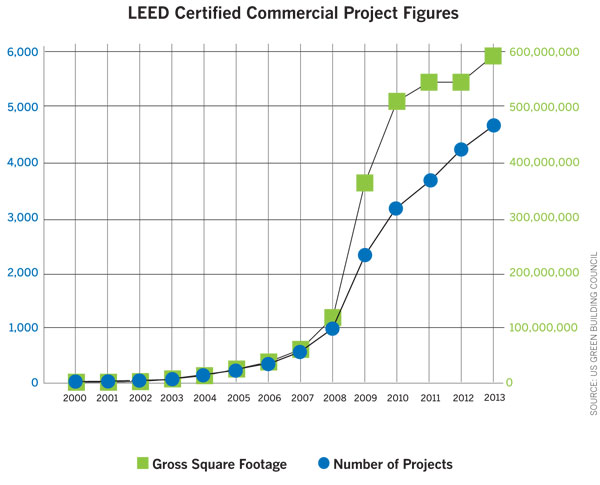

Green certifications also continue to attract building owners. More than 2.8 billion square feet of building space has now been recognized by the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) green building certification program, according to the US Green Building Council. The gross square footage of LEED-certified commercial projects in 2013 alone reached 597 million, a more than 500% increase from 119 million in 2008.

Past the Hype

There’s really no such thing as a risk unique to green building; familiar risks are instead merely compounded by what is unique about green building. For example, the frenzy of 2008 and 2009 resulted in riskier behavior and the potential for unfulfilled expectations.

“We’re seeing more and more hype that creates unrealistic expectations and contracts that create obligations that are unrealistic, unattainable, or countermand professional judgment,” Senior Risk Management Attorney at Victor O. Schinnerer & Co. Frank Musica told PE magazine in 2008. The hype, he said, was leading design professionals to ignore their normal risk management procedures, putting themselves in situations that caused them numerous problems.

Today, design professionals are more cautious and owners more informed, according to Musica. “What was happening was a lot of design firms, especially architects but I think engineers too, would jump in there and say, ‘Yes, we can do this,’ because they were enthused by green building,” he says looking back. “Now I think they’re going into it with more of a mindset of…if you’re working with us and you’re willing to hire contractors who know what they’re doing, we think we can get it to this level.”

Unskilled contractors, as can be ascertained from Musica’s statement, remain one of the more significant risks in green building. Steven Straus, P.E., president of engineering consulting firm Glumac, informed PE magazine of this in 2008 and still considers it a problem.

“That’s a big problem in our industry,” he says. As green technology becomes more mainstream, subcontractors are expected to know the technology and how to implement it, Straus explains. But when they don’t, “they will act like they know what they’re doing and potentially fail, creating huge problems for the industry.”

Among the services Glumac provides is building commissioning, which gives the firm firsthand experience with the problems that arise as a result of unskilled contractors. “We are finding just unbelievable issues of work not being done in accordance with the documents,” Straus says. One of the ways Glumac catches problems and ensures they are resolved is by tracking energy for the first several years of a building’s operation.

When in doubt, Glumac also mitigates risk by requiring contractors to complete mockups and test them prior to tackling an entire project. Straus recalls one contractor who said they could handle a project with a raised access floor and plenums that Glumac required to build a 4,000-square-foot mockup first. “We did that and they had 50% leakage” he says. “It became very apparent that they didn’t understand what the drawings and specs were requiring for them to seal that underfloor plenum, and so they had to go back and do that until that mockup passed.”

Government Grief

While one of the more significant risks, unskilled contractors aren’t the number one risk in green building for design professionals right now, according to Straus. Instead he considers it to be something Musica cautioned design professionals about in 2008—contractual requirements to achieve certain levels of certification, such as LEED Gold. “A design team can’t obtain that,” Musica said then. “It takes more than the design elements to do that.”

“I’d say the number one risk in green design relates to government projects where there is a contractual obligation to achieve a certain LEED rating,” Straus says. “This is a very difficult situation, because it’s not just one party’s responsibility—the owner has responsibility, the design team has responsibility, the contractor has responsibility. There are a lot of different parties that have responsibility to actually achieve LEED certification, and if those parties don’t collaborate and work together and they don’t achieve the certification level that has been required by the contract, there can be some complications and potential litigation.”

“When it comes to LEED certification there is an independent body that makes that determination,” adds Christopher Nutter, director in the Global Construction Practice of Navigant Consulting. “Whether you’re promising a particular LEED rating or a particular performance level, you can only promise things that you have control over.”

There is obvious financial risk as well, especially with design-build projects that have a certification requirement. “What happens is the general contractor bids the work based on some assumptions that are made during the competition phase,” Straus says. “As the project design starts to evolve, the requirement to include certain LEED elements becomes necessary to achieve a certain LEED rating, and sometimes the contractor doesn’t anticipate all the costs that are associated with that.”

It doesn’t end with contractual obligations for government projects, according to Nutter. The adoption of legal standards and green building codes means legal risks are taking hold as well, and not just for those working in green building, but anyone working in construction.

“What really seems to be happening now is there are obviously voluntary standards like LEED, there are local adoptions of voluntary standards that actually make them legal standards for those local jurisdictions, and there are adoptions of green building code, which are either complimentary to or in excess of whatever some of the voluntary standards would be,” he says. “Today that’s probably the greatest risk, just understanding what the requirements are and fulfilling them with your design.”

Adding to the risk is that many local jurisdictions have adopted a mishmash of codes and standards, Nutter adds. “It can be hard for the design professionals to understand what the design requirements they’re supposed to meet are.”

What’s New

A final area of risk in green building comes from using new technologies. Some may be harder to get and cause delays, some may be untested, and manufacturer testing may not be enough.

“Clients don’t like engineers ‘experimenting’ on their projects, and frankly there are a lot of design firms that are using clients’ projects as experiments,” Straus says. “I think that’s completely inappropriate. Owners are expecting to have tried-and-true methods applied to their projects. Some owners are willing to take on a little more risk in utilizing innovative technologies, understanding some of those risks, but they certainly don’t want experiments conducted on multi-multimillion or even billion-dollar projects.”

“We’re also seeing science and courts suggesting things are so technically complex, you as a design firm cannot simply rely on what manufacturers tell you,” Musica adds. “So you have an independent duty. How far that goes depends on the arguments and the situation.”

“If there’s more and more claims like that—you owe us a duty to look more closely into whatever that product features, whatever energy it encompasses, whatever availability there really is—that really opens up a lot of risk for design firms,” he continues. “That would be fine if they’re getting paid to do the research, but they’re not.”

None of this is to say engineers and other design professionals can’t experiment with new technologies. There are just less risky and more ethical ways to go about it. Glumac, for example, tests advanced designs and new technologies on the firm’s own offices.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field.

Volunteering at NSPE is a great opportunity to grow your professional network and connect with other leaders in the field. The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day:

The National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) encourages you to explore the resources to cast your vote on election day: