August/September 2013

Debt Overload

Many college graduates carry a heavy student loan burden. How are young engineers being affected?

BY EVA KAPLAN-LEISERSON

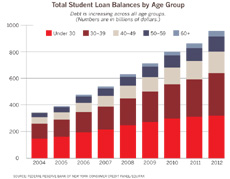

Every day, another news article—or five—appears: Student loan debt is piling up. The national total almost tripled between 2004 and 2012, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The figure currently tops $1 trillion, and student loans are now the second-largest form of consumer debt, after home mortgages.

Every day, another news article—or five—appears: Student loan debt is piling up. The national total almost tripled between 2004 and 2012, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The figure currently tops $1 trillion, and student loans are now the second-largest form of consumer debt, after home mortgages.

In addition, the federal student loan interest rate was recently a subject of heated debate, as the rate doubled to 6.8% on July 1 before Congress passed a retroactive fix later that month.

Some are calling student debt the next big financial crisis. But what are the implications for engineering students? Upon graduation, they will be among the highest paid professionals. Is debt a serious issue for them? And what will be the effects on the profession and society as a whole?

Ups and Downs

Several key factors have contributed to the amount of debt nationwide: growth in the number of students attending college, college costs that have increased steeply, and decreases or stagnation in government aid.

The percentage of Americans in their mid-20s who held at least a bachelor's degree jumped from a quarter to almost a third between 1995 and 2011, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

But college costs more than in the past. The College Board, an educational association, reports that over the last 30 years, average tuition and fees at private four-year schools rose by 167%, at public two-year colleges by 182%, and at public four-year institutions by 257%.

In recent years, many states in budget crunches have also cut funding to public institutions. Additionally, the purchasing power of federal Pell grants has not kept up with college cost increases.

NSPE President Robert Green, P.E., F.NSPE, undergraduate coordinator in Mississippi State University's college of engineering, believes that "much of the 'perceived' rise in college costs is really shifting the burden of fewer governmental resources to parents." But in the economic downturn, parents also have less money to spend on their children's education.

While some people characterize the current situation as a crisis, Megan McClean, director for policy and federal relations at the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators (NASFAA), doesn't necessarily agree. The $25,000 average college debt is manageable for students over a 10-year repayment plan, she asserts.

The students who find themselves in the news because they are saddled with six figures in student debt are outliers, the policy director stresses. Student loans are an investment in education, and she wants to reinforce the message that "borrowing can be done in a reasonable way."

The Engineering Outlook

A 2013 report by loan provider Sallie Mae offers some statistics specific to the engineering major that may help ease the mind of students.

First, the report notes that although engineering students paid the second-highest total for college, they borrow the least of the majors studied. This may be due to the push to create more engineers and subsequent aid to help do so.

In addition, engineering students can expect to earn top dollar after graduation. In the National Association of Colleges and Employers' 2013 salary survey, engineers secured seven of the 10 top-paying slots. Graduates made an average starting paycheck of $62,535.

However, Green points out that engineering programs often require more coursework to earn a bachelor's degree, which may push up cost and debts. In addition, he notes that the change to the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying's Model Law to require an additional 30 hours of education for licensure starting in 2020 could add to the debt load if enacted by states.

In the past, assistantships and stipends have helped pay for engineering students' master's degrees, but Green explains that this model may not hold if more students pursue additional education and compete for funding.

On Their Minds

In PE's small unscientific poll of engineering students and recent graduates, about half said they were not concerned about student debt. They felt optimistic about fast-growing careers, had parents assisting them, or were receiving military benefits.

The rest of the respondents said they were worried about debt or had made changes to their lives to address the issue.

Some saw debt as a "necessary evil." For instance, Jayss Marshall, a rising sophomore attending community college to lower costs, applied for his first student loan this summer. Marshall is considering either aeronautical engineering or materials science and engineering at a California state school. He dislikes the idea of debt, but says, "I will do what I must to continue moving forward." Still, doubts creep into his mind about his job prospects after graduation.

Two students noted that although student debt would not affect their careers, it did affect their personal lives. Chris DeDene, a graduate fellow in the University of Minnesota's civil engineering department, explains that he's delayed purchases such as a new car and a house because debt has interfered with his disposable income.

Scott Malinoski, a 2013 Rutgers graduate with a civil engineering bachelor's degree, has also put the brakes on spending while job searching, although his prospects have been good. "Even if my 'earning potential' promises that I can pay for a trip to Bora Bora soon, it is just that, potential," Malinoski says. He plans to live with his parents for a few years to save money.

Brock Wiberg, a mechanical/aeronautical engineer, completed both a BS and MS degree without debt and even paid for his wife's BS degree through his scholarships, internships, and part-time work. He says he "literally took the cost in the teeth as I went."

A degree isn't a promise of employment, Wiberg emphasizes. He explains that many of his "very capable" classmates are still looking for work nearly a year after finishing their BS. "Everyone wants an engineer with three-plus years of experience," he says.

The engineer also believes that graduates can't rely on their earning potential to outweigh their debt anymore. That's changing, he says; the increase in tuition is outpacing the additions to salary.

Diversity and Debt

The issues of cost and debt can be even more pressing for students from low-income backgrounds. Some schools charge engineering students higher tuition to pay for labs and equipment; although that cost can be offset by increased financial aid, research suggests negative perceptions of differential tuition may still affect those students' willingness to join engineering programs. That can hinder diversity in the profession.

|

Total Student Loan Balances by Age Group |

Low-income students who do enroll in engineering programs are more likely to work while in school to help meet costs, which can affect college completion rates. Chris Smith, director of research and program evaluation for the National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering (NACME), explains that students who work 15 hours or more a week are less likely to complete their degrees. "It just becomes very difficult to balance everything," he says. "These are some of the barriers really affecting low-income students, underrepresented minorities in particular."

Minorities, whose families disproportionately earn lower incomes, accrue more college debt as well. For instance, Smith points to a 2009 study from the National Center for Education Statistics in which 28% of African American students reported $33,500 or more of undergraduate debt compared to 15% of Caucasian students.

"It's very difficult for students to know what the consequences of these loans will be once they graduate," says Smith. "It almost seems like fake money once they're on the college campus."

Travis Simerly, a self-described low-income student who enrolled in a Tennessee community college at age 34 after his work as a brick mason dried up, plans to transfer to Tennessee Tech University to complete a mechanical engineering degree. He has paid cash out of pocket and is hoping to secure grants and a student loan.

Although he currently has a 4.0 grade point average, Simerly is concerned about the availability of aid for an older student, as well as paying back loans while job searching. "When it comes down to it," he asks, "do you want to default on the loan or pay bills and eat?"

Although federal loans offer ways to halt payments during periods of unemployment, interest may still accrue, prolonging the time required to pay off the loans. And private loans offer fewer options.

Simerly says he's heard from recent engineering graduates who are shocked by the large minimum payments and high interest rates of their loan bills. "I've heard from several friends that they had no idea that they'll be paying off their debt until they die," he says.

Some schools are taking bold steps to ease the way for low-income students. NACME's Smith points to institutions such as Princeton University, Rice University, and the University of North Carolina that are eliminating loans from the financial aid packages of students from low-income families. This is an "innovative and helpful solution," he says.

But only those schools with very large endowments can do this, and Smith says the practice is unlikely to be adopted by schools with fewer resources.

In contrast, a recent report from the New America Foundation, a public policy institute, found that hundreds of colleges and universities asked low-income students to pay amounts that were large proportions of their families' annual incomes.

Nearly two-thirds of the private institutions charged students from families making $30,000 or less annually a net price of more than $15,000 a year. At the same time, they provided deep tuition discounts to wealthier students to bring in high-achieving students. Public colleges are increasingly using similar tactics, says the foundation.

According to Undermining Pell: How Colleges Compete for Wealthy Students and Leave the Low-Income Behind, the high costs of education leave low-income students no choice but to take on high amounts of debt, work full-time (increasing the chance of dropping out), or leave school until they can afford to return.

Some students take out loans and then drop out of school because they're working too many hours or struggling academically. These engineering students are the ones Robert Green is concerned about. "They're then in a situation of having no degree, having a relatively low-paying job, [and] having to pay loans but with perhaps no ability to do so," he explains.

Although Green believes that incurring debt for an engineering degree is a viable and not unreasonable option, students who do so need to have the ability and commitment to complete the program, he says.

The Big Picture

Student loan debt doesn't just affect individuals; it also ripples through society. When students can't spend on cars, houses, or other luxuries, the economy takes a hit. Debt can also interfere with entrepreneurship and small-business growth, explained the student loan ombudsman for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in an article in Politico. That could mean fewer companies launched by young engineers and fewer jobs created.

|

Costs and Debts by Major |

Many solutions have been proposed to address the student debt situation. For example, the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators released a report reimagining the way student aid could work with a list of policy considerations (not recommendations).

They include restructuring the way Pell grants work with a Pell Promise that would let students know as early as eighth grade if they are eligible for the grants and guarantee them (perhaps incentivizing student achievement), and a Pell Well that would give students a set amount of money they could draw down following their own schedule. Other ideas: implementing automatic income-based repayment plans, which students currently have to opt into; and providing students with information about future wages when they are considering majors.

Among the more controversial considerations is requiring students to meet an academic threshold for student loan eligibility. "Is it the responsible thing to have [students] borrow if they're not successful in high school?" asks Megan McClean. But this step could disproportionally block low-income and minority students from securing aid and enrolling in higher education.

McClean stresses that more data is needed, and an academic researcher is exploring that possible effect. If it turns out that the strategy would have an uneven impact, "it may not be the best idea," the policy director says.

Some states are trying innovative ideas to address student loan debt. In July, the Oregon legislature unanimously passed legislation to implement a pilot program allowing students to attend state universities for free if they pay a percentage of their later incomes over time toward tuition for future students. The bill is expected to be signed into law by the governor.

Vermont's STEM incentive program provides recently hired graduates who work for qualified companies $1,500 annually for five years to help pay off student loans (see December 2011 PE). And New York's Empire Engineers Initiative Act would provide student loan forgiveness awards for up to 50% of tuition to engineering graduates who work for participating companies for five years. The effort aims to increase the number of engineers in the state.

Federally, the 2008 Higher Education Opportunity Act included a provision for up to $10,000 of student loan forgiveness for "areas of national need," including STEM fields. The American Council of Engineering Companies pushed for the inclusion of STEM workers among other professionals such as childhood educators, nurses, and public sector employees. However, after the economic downturn, the plan was never funded.

"We haven't given up on it," says Alan Crockett, ACEC's director of communications and media. "Anything to help students go into these fields just benefits the entire nation. This is very important to us and engineering students." Crockett hopes that as the economy picks up, the initiative will be revisited.

But experts point out that in addition to plans such as these, students need better education on financial literacy, although it's unclear who should take responsibility for this. "Education and a student awareness program towards loans and the real-life consequences are very helpful," says NACME's Smith. "The mindset is certainly different when you're enrolled compared to when you're out of college and trying to figure out a way to pay off [loans]."

NASFAA's McClean brings up the term fit, which is often bandied about in the admissions arena in which she used to work. For instance, does a school have the right major or is it located where a student wants to be? "I like to drive home that cost is also part of fit," says McClean. "There are lots of options." Students need to think ahead about what they're borrowing and ensure that it's a reasonable amount, she stresses.

Debt's Effects

View Larger